Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

KFF data and analysis is essential to anyone seeking to understand the U.S. healthcare system. It’s copious, reliable, and clearly presented. But inevitably, it’s not always up to date.

In late 2024, KFF posted a calculator estimating how much more ACA marketplace enrollees at any income, income and family size would pay for coverage in 2026 if the subsidy enhancements created by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) are allowed to expire (they are funded only through 2025). If the ARPA subsidy schedule expires, which appears near-certain at this point, the subsidy schedule will revert to the pre-ARPA formula used through OEP 2021, adjusted by an annual inflation factor.

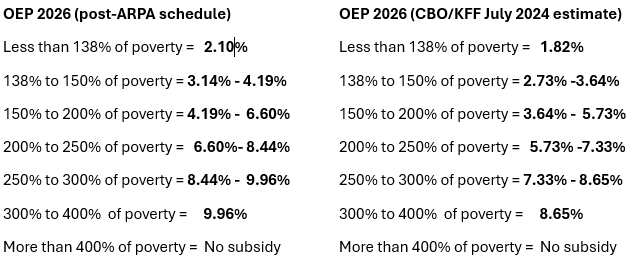

When the calculator was created, the subsidy schedule for 2026 was unpublished, and KFF used estimates created by CBO and the JCT in June 2024 (see p. 9 here). Last month, the IRS published the subsidy schedule for 2026, and the CBO estimates turn out to have been quite low. At higher incomes, the actual percentage of income required to buy the benchmark (second cheapest silver) plan is more than a full percentage point higher than CBO estimated (e.g., 9.96% of income at an income of 300% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) vs. the CBO estimate of 8.65%).

Percentage of income required to purchase a benchmark silver plan at different income levels in Plan Year 2026: Actual vs. KFF/CBO 2024 estimate

Sources: IRS, KFF, CBO. See note at bottom for the ARPA enhanced subsidy schedule.