Note: Free xpostfactoid subscription is available on Substack alone, though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

|

| Will Plan Year 2025 forever be Obamacare's Babe Ruth? |

Charles Gaba has issued a timely warning that most of the enrollment loss in the ACA marketplace this year, resulting from expiration (so far) of the enhanced premium subsidies funded only through 2025, will only be evident after CMS releases its first snapshot of effectuated coverage — that is, paid-for coverage. Thanks to auto re-enrollment, enrollment losses will look relatively slight (perhaps minus 1 million) as of the end of the Open Enrollment Period.

Republicans will make hay of this — claiming, as CMS did, that the subsidy reduction is not so catastrophic for the 93% of enrollees subsidized in 2025 who will remain subsidy eligible in 2026. And CMS’s annual snapshot of coverage effectuated as of Feb. 1 typically doesn’t appear until June or July. At that politically distant point, much more of the fallout from expiration of the enhanced subsidies will become visible.

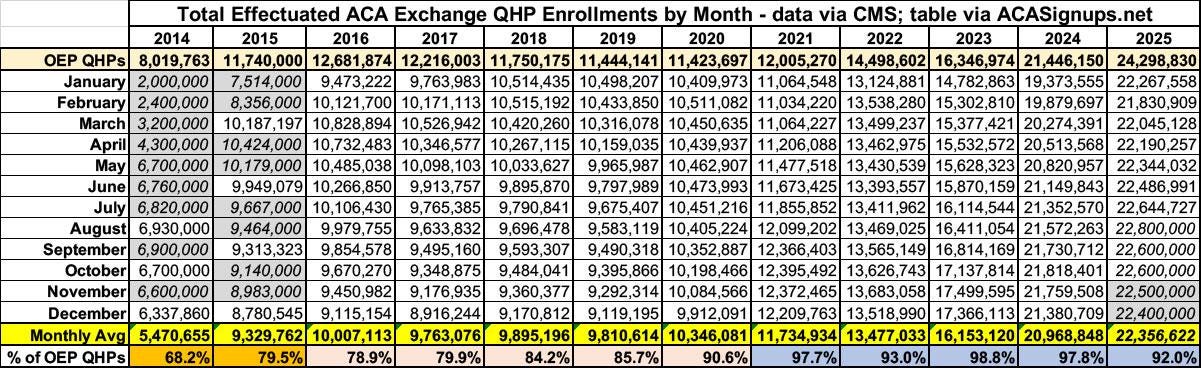

In 2024 and 2025, early effectuated coverage exceeded 95% of end-of-OEP enrollment, whereas in 2016, it was just 85%. Retention improved during the first Trump administration, probably for reasons including 1) a shortened Open Enrollment period and cuts to funding for enrollment assistance and outreach, which likely discouraged more marginal enrollees from enrolling at all, and 2) Trump’s cutoff in October 2017 of direct reimbursement of insurers for the Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) subsidies that attach to silver plans at low incomes, which triggered silver loading (the pricing of CSR into silver plan premiums) and increased the number of enrollees paying zero or very low premium. Retention increased further after the enhanced subsidies enacted by the American Rescue Plan Action March 2021 made zero-premium coverage much more widely available — to the point where, in 2025, about a third of all enrollees paid zero premium.

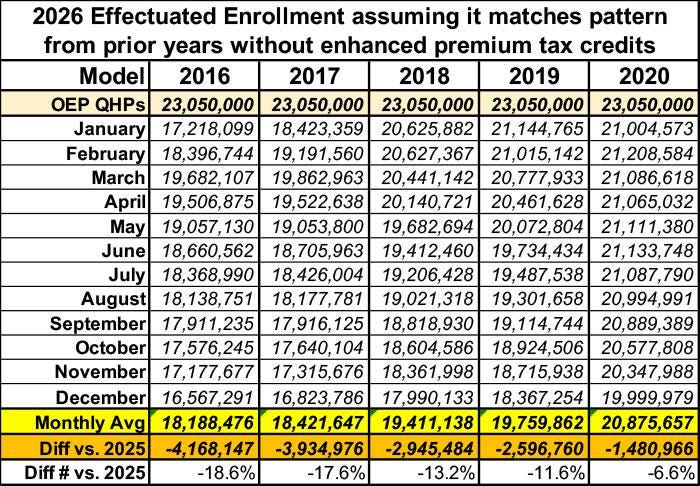

There’s reason to believe that massive sticker shock when the first 2026 premium bills arrive — with subsidized premiums for a benchmark silver plan more than doubling on average from 2025 to 2026 — will drive the ratio between OEP enrollment and February effectuated enrollment back to Obama-era levels this year, or even lower. Further, since Republicans have terminated year-round enrollment for enrollees with income below 150% FPL, average monthly enrollment in 2026 will drop even further compared to 2025. That change won’t be evident until mid-year 2027.

Read Gaba on this. He’s sharp on the political ironies (with advocates of the enhanced subsidies now echoing Republicans’ 2014 cry of “but how many have paid?” as the ACA’s first enrollment period wound down), and he roughs out credible estimates, roughly matching CBO’s, of enrollment losses in 2026 as reflected in average monthly enrollment (about 4 million). What I want to do here is consider another important effect of reduced subsidies: The likelihood that many who remain enrolled will downgrade their coverage to reduce their premiums. How might we measure the combined effects of increased uninsurance and increased under-insurance?

To get a grip on any future degradation of coverage obtained in the marketplace, we can use actuarial value (AV) — in combination with effectuated enrollment. AV is the percentage of the average enrollee’s costs a plan is designed to cover, calculated according to a formula created by CMS.*

Average weighted AV in the entire national marketplace has been stable over the years at 78-79% (compared to about 84% in employer-sponsored coverage), though the factors determining the average have been quite volatile. More on that stability/volatility below. If the enhanced subsidies are not renewed, I believe average AV as well as total enrollment will drop in 2026 and years following. To get a sense of the effects of dropped coverage and degraded coverage, I propose a measure something like “OPS” in baseball — a combination of on-base percentage and slugging percentage. The measure would simply be “Total AV” — total enrollment times average weighted actuarial value. The best measure of total enrollment, although it entails an 18-month data lag (under current practice), would be average monthly enrollment. An alternative measure, available roughly six months after the end of each OEP, would be early effectuated enrollment (as of February).

In 2025, we have a figure for average monthly enrollment through September**: 22.4 million (22,356,622). As Republicans terminated year-round enrollment at low incomes (implemented by the Biden administration) as of August, there will probably be a slight drop in the full year total, when available, to perhaps 22.3 million. Average weighted AV was 79.0% (Total AV calculations require a bit of extrapolation, outlined in a note at bottom, from the Public Use Files published by CMS). Total AV for the marketplace in 2025 will thus be about 18.4 million — probably a permanent all-time high, if the enhanced subsidies are not restored.

Taking expected increased attrition into account, Gaba estimates that average monthly enrollment will drop to about 18.5 million in 2026. That’s a 17% drop from 22.3 million in 2025. If weighted average AV drops, say, from 79% to 75%, Total AV in 2026 will be 13.9 million— a 24% drop. That’s a fuller measure of what may be lost.

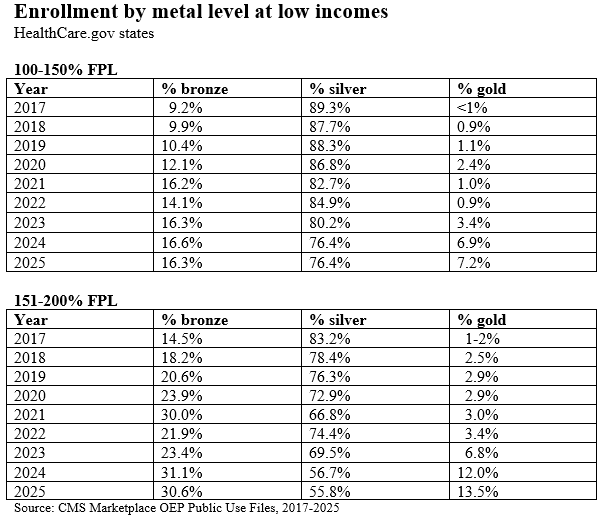

Average weighted AV: Stable in aggregate, volatile in composition

As to the shifting composition of average weighted AV in the ACA marketplace over the years: The chief source of high-AV coverage in the marketplace is the Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) that attaches to silver plans at low incomes, raising a silver plan’s AV to 94% at incomes up to 150% of the Federal Poverty Level and to 87% at incomes in the 150-200% FPL range — compared to 60% for bronze and 80% for gold. Over the years, silver plan selection at low incomes (those eligible for strong CSR) has eroded steadily, but the percentage of enrollees with income below 200% FPL has risen sharply. (A weak CSR is available in the 200-250% FPL bracket, raising AV to 73% . AV for silver plans without CSR is 70%.)

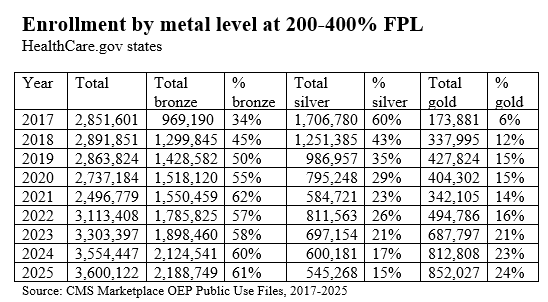

First, look at the rate of silver selection at the two highest CSR levels from 2017-2025. This is only in HealthCare.gov states, as in early years CMS data for state-based marketplaces was much less complete. Over this period, the number of states using the federal exchange dropped from 39 to 30. At the same time, all states that have refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion (excepting Idaho until 2020) used the federal exchange throughout these years, ensuring that enrollment in the 100-150% FPL income bracket has always been concentrated in HealthCare.gov states (In 2025, when just 30 states used HealthCare.gov, 85% of enrollees at 100-150% FPL were in Healthcare.gov states).

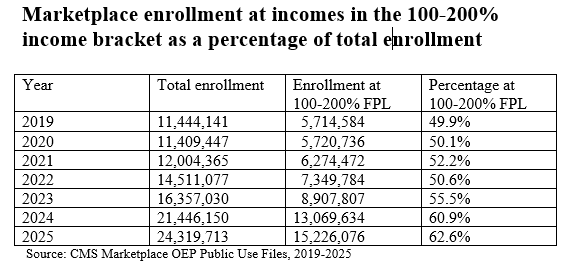

While silver selection at incomes where strong CSR (94% or 87% AV) is available has dropped, the percentage of enrollees at incomes below 200% FPL has risen steadily since 2019 (the first year in which CMS provided income breakouts for all states).

The percentage of all enrollees who obtained CSR hit an all-time high in 2017 at 57%, dipped to 53% in 2018 (the first year when silver loading went into effect), and was 53% in 2025. But not all CSR is created equal, and in the silver loading era, silver selection in the 200-250% FPL bracket, where CSR raises AV to just 73%, fell off a cliff. In 2017, in HealthCare.gov states, 16% of silver selection at CSR-eligible incomes was in the 200-250% FPL bracket; in 2025, that percentage was down to 3.5%. Conversely, in 2025 78% CSR enrollment was in the 100-150% FPL bracket, compared 52% in 2017. In 2025, in HealthCare.gov states, 41% of all enrollees — 7 million out of 17.1 million — obtained CSR with a 94% AV.

A word about enrollment at income below 100% FPL, the income threshold below which marketplace subsidies are unavailable for citizens. CMS did not break out this income bracket until 2022. In 2025, there were 548,650 enrollees in the under-100% FPL bracket, 2.2% of all enrollment. Most of them were lawfully present noncitizens subject to the “5-year bar” to Medicaid eligibility to which U.S. law subjects noncitizens. The ACA stipulates that immigrants subject to the 5-year bar are subsidy-eligible in the marketplace even if their income is below 100% FPL. But the Republicans’ vile megabill enacted this summer stripped out this eligibility as of Jan. 1, 2026. CBO estimates that about 300,000 immigrants will lose coverage as a result — and most of them were probably enrolled in high-CSR silver. That’s one more ding to average AV (as well as enrollment) in 2026 and years following, even if the enhanced subsidies are extended.

The other major change in the distribution of AV over the years derives from silver loading — the pricing of CSR directly into silver plan premiums, adhered to in varying degrees in different states and rating areas, or by different insurers within states and rating areas. Because ACA premium subsidies are designed so that enrollees pay a fixed percentage of income (varying by income bracket) for the benchmark (second-cheapest) silver plan, when silver premiums rise, so do subsidies, and so do “spreads” between the benchmark silver plan and cheaper plans — e.g., most bronze plans, and in some states, many or most gold plans. Since insurers tend for competitive reasons to underprice silver plans (as silver remains the dominant metal level, since most enrollees qualify for strong CSR), an increasing number of states are mandating that insurers price plans in strict proportion to actuarial value. Since silver plans, enhanced by CSR for most enrollees, have higher AV than gold plans, gold plans should be cheaper than silver - -and in 20 states in 2026, lowest-cost gold plans are on average priced at premiums below that of the silver benchmark.

Weak or strong silver loading has been in place in almost all states since 2018, and as a result, silver plan selection has collapsed at incomes over 200% FPL (where CSR is weak or unavailable) as well as eroding at incomes under 200% FPL. Note above that gold plan selection as well as bronze plan selection has increased at low incomes. Much of the gold selection increase is concentrated in Texas, where gold plans are far cheaper than silver. In 2025, almost 900,000 Texas enrollees with income under 200% FPL enrolled in gold plans. That’s about 6% of all enrollees with income under 200% FPL nationwide.

Low-income enrollees who select gold plans are giving up AV, often in exchange for a reduced premium (e.g., to obtain coverage from an insurer whose silver plan is priced above benchmark). The difference in AV is reflected most dramatically in the annual out of pocket maximum .By statute, out-of-pocket maximums are capped at a much lower level for CSR-enhanced silver plans available to those with income under 200% FPL than for all other plans, including gold. In 2026, the highest allowable OOP max for silver plans at incomes up to 200% FPL is $3,500, compared to $10,600 for other metal levels. For enrollees with income below 150% FPL, silver OOP maxes are usually far lower than $3,500, averaging $1,738 in 2026, according to KFF.

At incomes over 200% FPL, the window in which the premium difference between silver plans and bronze plans is worth the higher AV provided by silver plans is very narrow — and again, in many states, at least some gold plans are cheaper than benchmark silver. Silver selection at incomes over 200% FPL has appropriately collapsed. Here is the breakout in HealthCare.gov states:

With respect to average weighted AV, the increase in gold selection in this income bracket only partly offsets the larger increase in bronze selection. But again, inflated silver premiums more often than not make bronze a better value than silver at incomes over 200% FPL.

Why enrollment has doubled and silver plan selection has diminished

The story of why enrollment surged after ARPA was enacted in March 2021 is in one sense straightforward: ARPA made high-CSR coverage free to enrollees with income up to 150% FPL, increased premium subsidies in every income bracket, and lifted the income cap on subsidy eligibility. But the story is somewhat complicated, for better and worse, by surging broker participation in those years. The number of brokers registered with HealthCare.gov rose from 49,000 in 2018 to 83,000 as of OEP for 2024. Since Americans remain persistently ignorant about what’s available in the marketplace until they need it, increased broker outreach was probably key to the doubling of enrollment in the post-ARPA era. At the same time, broker fraud also metastasized around 2023-2024. A CMS crackdown and rule-tightening has probably reduced such fraud but has not yet quelled it, to judge from broker discussion sites I tune into. Brokers enrolled probably some hundreds of thousands of people without their knowledge or consent — the totals are still unknown — and engaged in unauthorized plan switching — sometimes multiple times — for hundreds of thousands more. (The switching may have slightly pushed average AV down slightly, as fraudster brokers looked for zero-premium plans to switch enrollees into, and most of those would be bronze plans.)

The story of why silver selection has eroded at incomes under 200% FPL is more complicated. As more low-income enrollees have poured into the marketplace in the enhanced subsidy era, some may simply make mistakes. The number of available plans in each rating area has proliferated; the average enrollee is confronted with more than 100 choices. Most enrollments are broker-assisted, and there is a fair amount of low-quality and sometimes corrupt brokerage, though I know of no source or means to assess broker quality norms (a good broker is priceless, given our ridiculously complex marketplace, and there are plenty of good ones). At the same time, I have delved more than once into the probably-increasing incidence of enrollees choosing lower-AV coverage with eyes wide open, in order to obtain coverage from a plan with a more robust provider network or a formulary that covers the enrollee’s drugs. Competition has pushed the marketplace toward narrow networks, especially at the lowest premiums at each metal level, and that has probably induced more enrollees to trade AV for network or formulary quality.

In any case, expiration of the enhanced subsidies is likely to accelerate the erosion of CSR takeup. An option to take some or all of the premium subsidy as an HSA would of course further erode AV, trading first-dollar coverage for increased exposure to high out-of-pocket costs. Total AV for the marketplace is therefore likely to erode even faster than total enrollment if subsidies remain at current levels.

— — — — —

*AV is in one sense a misleading measure, in that the average is skewed by the small percentage of enrollees in any plan who incur very high costs (capped for the enrollee by the out-of-pocket maximum, which this year can be as high as $10,600). If your plan has an AV of 60% and covers essentially no costs before, say, an $8,500 deductible, but you’re in an accident and incur $100,000 in medical costs, if the out-of-pocket maximum is $10,000, 90% of your costs are covered. For many other enrollees in such a plan, AV may be effectively zero, even if they spend thousands of dollars out of pocket. That said, AV is a uniform measure that does indicate the relative value from year to year of marketplace coverage.

**See Gaba, who posts a table combining 6 months of effectuated enrollment for 2025 available here (find “January-July effectuated enrollment tables” for 2025) with August and September estimates provided in CMS’s monthly Medicaid and CHIP enrollment snapshots.

A note on average weighted AV calculations. The marketplace Public Use Files for 2022 through 2025 break out enrollment at each CSR level for HealthCare.gov states but not for all states. As a proxy, I used the breakouts of metal level enrollment by income in the “State, Metal Level and Enrollment Status” PUF, taking silver totals as a proxy for CSR levels, subtracting the difference between total CSR enrollment (provided for all states) and total silver enrollment at incomes from 0-200% FPL proportionately from each CSR bracket.

For 2017, I had to get a bit more creative, as metal level selection by income was broken out only for HealthCare.gov states, though the PUF does show total silver enrollment in both HealthCare.gov states and SBM states. To estimate the distribution of silver selection by income in SBM states, I used the “SBM-FPs” — nominal state marketplaces using the federal exchange — as a proxy, since all four of those states had expanded Medicaid. I then calculated an average silver AV for HealthCare.gov states (84.6%) and SBM states (80.7%) and used those averages for total silver enrollment in each of the two categories.

Edited 1/9/25 -- including correction of a typo regarding avg. monthly enrollment in 2025 (estimated at 22.3 million, not 23.3 million).

Public domain image: Wikimedia Commons