Attention xpostfactoid readers: All subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free). I will continue to cross-post on this site, but I've cancelled the follow.it feed (it is an excellent free service, but Substack pulls in new subscribers). If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up!

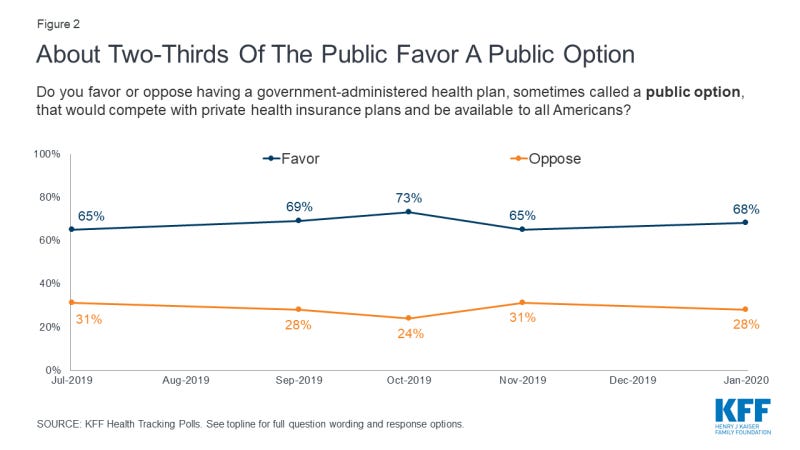

In polling about U.S. healthcare, the prospect of a “public option” for health insurance, open to all Americans regardless of whether they have access to employer-sponsored insurance, generally scores high. Here is the top-line response to a Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll conducted in January 2020:

Looking beneath the hood of that apparent relative consensus, a research team led by Adrianna McIntyre of Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health conducted a poll in November/December 2020 that probed attitudes toward government that underlie responses to health reforms including a public option — specifically, a Medicare buy-in for people under age 65. The researchers published an analysis* in Milbank Quarterly this month. While top-line results were similar to KFF’s, the researchers note:

An overwhelming majority of Democrats (86%) report believing that it is the government’s responsibility to ensure universal health insurance coverage; only 11% of Republicans hold the same view. Most Democrats (71%) also report that they would prefer a health insurance system run mostly by the government, while a similar share of Republicans (78%) would prefer a system based mostly on private health insurance. Two-thirds of Democrats (67%) believe the federal government should be more involved in health care in the future, but over half of their Republican counterparts (56%) believe it should be less involved. Prior work has also found that while a large majority of Democrats (65%) believe the government would do a better job than private health insurance plans at reducing the nation’s health care costs, significantly fewer Republicans (25%) hold that view.

These divisions make the authors skeptical as to the prospects of establishing a public option, especially given the powerful industry interests that view the public option as a threat either to their existence in current form (insurers) or to the commercial payer gravy train (providers). They posit that consolidation within the healthcare industry in recent years “may actually make industry actors more formidable foes to health reforms that they view as detrimental to their interests than they had been in 2009.”

McIntyre et al. suggest that the political divide underlying apparent strong top-line support makes it unlikely that a reform of this kind can pass with bipartisan support, which until the Obama years was widely considered essential for transformative legislation. On the other hand, citing Democrats’ 2022 passage on a party-line vote (with a razor-thin majority) of legislation empowering Medicare to negotiate select drug prices, the authors allow that a broadly available public option might ultimately become law on a similar basis.

This paper’s exposure of “wide partisan attitude gaps…under a surface of broad support” is illuminating. In a way, though, it seems to me that a public option open on an affordable basis to all who want or need is at least conceptually aligned with a political reality in which, with respect to a public option,

Democrats seem to put the emphasis on public—overwhelmingly supporting a stronger role for government in health care. In stark contrast, Republicans may internally emphasize option—supporting the policy only insofar as it represents expanding the choice set in a mostly private market.

With a very large caveat, it’s possible to read the history and current state of Medicare as evidence that a hybrid system can (and does) exist that offers some satisfaction to both the Democratic and Republican propensities outlined above. Medicare provides one benefit of “public” ownership that all enrollees — and all taxpayers— benefit from: effective government control over provider payment rates (albeit with arguably excessive provider input). For those who choose traditional, fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare (e.g., those who can afford or have access to employer-subsidized Medigap), “public” FFS Medicare offers two other powerful benefits: near-unlimited choice of providers, and freedom from the sometimes onerous restrictions of managed care (prior authorization requirements and more frequent coverage denials or limitations, e.g. in post-acute care in particular). On the Republican side of the equation, our national infatuation with markets has led to an almost insane proliferation of choice among private options — e.g., of an average of 39 Medicare Advantage plans, or, on the “public option” side, a similarly baffling array of Part D prescription drug plans and Medigap plans, which are all private.

The caveat: policy choices have tilted the field so heavily toward Medicare Advantage that the equipoise outlined above is an endangered species. Those policy choices include failing to plug major holes in FFS Medicare coverage — chiefly the lack of a cap on out-of-pocket expenses — and payment formulas generous enough to MA plans to enable them to offer almost irresistible advantages to non-affluent enrollees who lack subsidized access to Medigap or who are not low-income and asset-poor enough to be dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. More than 60% of MA plan enrollees pay no more than the statutory Part B premium for coverage that includes a cap on out-of-pocket costs, a Part D plan, and ancillary services. That means their premiums are typically less than half of the combined premiums of Medicare Parts B and D plus Medigap. MA plans also offer ancillary services, usually including at least limited dental, vision and hearing coverage, that MedPAC values at $2,000 per enrollee per year. Those lower up-front costs and extra benefits are offered in exchange for higher out-of-pocket costs (compared to FFS + Medigap), limits (large or small) on choice of providers, and exposure to prior authorization and more frequent coverage denials.

As MA offers a deal that a rapidly growing share of enrollees feel they can’t afford to refuse, its market share has grown by leaps and bounds in recent years and now stands just below half of all enrollees. If current trends continue, FFS Medicare may lose its capacity to serve as a benchmark for federal payments to MA plans, which would untether the rates MA plans pay providers from Medicare rates set by CMS.

As McIntyre et al. point out,

This set of circumstances suggests that decisive and sweeping action would be required to level the playing field and slow the march of Medicare Advantage, which may be necessary to preserve the public Medicare program as a likely vehicle for future coverage expansions.

That said, the equipoise that has existed for 20 years between MA and FFS Medicare is at least imaginable for the healthcare system as a whole — and has been imagined in a number of proposals and bills. Early iterations of such a "public option" include Helen Halpin's CHOICE program (2003), Rep Peter Stark's Americare bill (2006),and Jacob Hacker's Health Care for America plan (2007). All of these enabled any individual to buy in on an income-adjusted basis regardless of whether her employer offered insurance, and gave employers the option of paying into the public plan (e.g., via a payroll tax) rather than offering their own plans. While Halpin’s plan was actually titled "Getting to a Single-Payer System Using Market Forces," Hacker’s (introduced as Democrats inched toward power) envisioned fruitful competition between ESI and the expanded Medicare program: A Lewin Group analysis of Hacker’s plan forecast that half of the nonelderly population would remain in employer-sponsored plans. More recently, the Medicare for America bill introduced by Reps Rosa DeLauro (CT-03) and Jan Schakowsky (IL-09) offers a revamped “Medicare” to all who want it — and implicitly preserves the employer market by mandating that providers accept a revamped Medicare payment schedule from commercial payers.

My point is that these plans reflect and attempt to accommodate the partisan ideological fissure that McIntyre et al. present as a potentially disabling condition. That’s not to say that McIntyre et al. are wrong. In fact, the prospects for anything like Medicare for America look very distant — endangered by the evolution of Medicare as well as by the fierce industry opposition recounted by McIntyre et al. To illustrate the latter, they cite the American Hospital Association’s attack on the public option in Senator Michael Bennet’s Medicare-X plan, which ring-fenced the public option within the ACA marketplace, making it available on a subsidized basis only to those who lacked access to employer-sponsored insurance. While the Medicare-X public option would be available to only a small sliver of the population — subsidized ACA marketplace enrollment totaled less than 10 million at the time the bill was introduced — providers regarded it as a camel’s nose in the tent (and the bill did provide for an opening to the small group market within a few years).

In fact it might be argued that our governments, federal and state, are losing the capacity and will to manage healthcare financing and delivery. That is, the increasing dominance of commercially-managed plans in Medicare and Medicaid, as McIntyre et al. imply, may be foreclosing on a true hybrid system. Perhaps our inability to implement rate-setting in FFS Medicare strong enough to fund less gap-ridden coverage creates irresistible pressure to impose managed care that squeezes high-value as well as low-value treatment. The ACO Reach program, which seeks replace the relatively passive claims management of the Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) with more actively managed care, indicates as much. Maybe, too, the lobbying clout of providers, insurers and pharma will effectively decide between Democratic and Republican ideological preferences, in favor of Republican.

On the other hand… there is the minor miracle of the prescription drug price negotiation (for a limited set of drugs) and inflation caps on drug prices included in the Inflation Reduction Act last summer. McIntyre et al. point to key differences between passage of this reform and the prospects for a public option: The drug price controls reduce spending rather than increasing it; they benefit all seniors, not just the poor (for which many voters read ‘minority’); and its polling support “seems substantially less malleable” than the public option’s.

Conversely, though, perhaps the drug price negotiation enacted in the IRA is a model for future reform, in that it both depends on government pricing power and applies that power in a commercially run market. Democrats also came within a whisker of applying the inflation caps in the commercial market. Government-imposed price control is perhaps the deepest underlying rationale for a public option — and the savings rate-setting would yield might share the “less malleable” support the public grants to drug price control.

In sum, the balance and tension between government and market control of healthcare in the U.S. mirrors — or is rather perhaps the largest instance of — the balance and tension between government authority and market forces in our society as a whole. By “balance,” I don’t mean to suggest “optimal balance.” In my view, the U.S. system has let market forces in healthcare — and the behemoths we’ve allowed those forces to breed — run out of control. A warning from a former health minister of Singapore, relayed in William Haseltine’s Affordable Excellence: The Singapore Health System (Brookings, 2013, free on Kindle) has stayed with me as a durable guiding principle:

Former Health Minister Khaw Boon Wan has said that the public sector should always play the dominant role in providing care services, but there needs to be a private healthcare system to challenge it. In his view, the public sector is necessary to set the ethos for the entire system— which should not only be about maximization of profits, a primary focus of the private sector. It is the public side that tends to set boundaries and standards for ethics within the system.

Khaw takes the view that where the private sector does dominate, it will inevitably influence the government and public policy to serve its own interests. If the public healthcare system is too small, it becomes the “tail that tries to wag the dog.” Once a private healthcare system becomes the dominant entrenched player, it is very difficult to unwind it— there are many vested interests and many pockets will be hurt. (Location 998--1007).

We are faced with that very difficult unwinding, as McIntyre et al. hammer home.

Postscript: One point at which the gravitational pull favoring the private market prevailed was in the ACA’s conception. McIntyre et al. recount how the public option included in the House bill was stripped out by conservative Democratic senators. Somewhat elided in their narrative is the question of why, by the time the ACA was drafted, the target population for what became the ACA marketplace was limited to those who lack access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance or other coverage. By 2009, what had happened to the broad “Medicare for all who want it” type plans described above, and introduced between 2003 and 2007? Short answer, as narrated in Jonathan Cohn’s The Ten Year War: Obamacare and the Unfinished Crusade for Universal Coverage: Massachusetts health reform, enacted in 2006 by Mitt Romney and the MA legislature, happened. The Massachusetts prototype, combining expanded Medicaid access and a marketplace of subsidized private plans for those who earned too much to qualify for Medicaid, provided proof-of-concept for a more limited initiative that could credibly cover most of the uninsured. And as Cohn recounts, at that point Congressional Democrats believed that they could win Republican buy-in to a scheme that relied in large part on the private market. None of the three major Democratic presidential candidates in 2007-2008 presented a health reform plan that seriously disrupted the employer-sponsored market or offered anything like “Medicare for all who want it.”

——

* Adrianna McIntyre, Robert J. Blendon, John M. Benson, Mary G. Findling, Eric C. Schneider, “Popular… to a Point: The Enduring Political Challenges of the Public Option.” Milbank Quarterly, Vol OO, No. O, 2023 (pp 1-23).

No comments:

Post a Comment