Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up!

.jpg) |

| Enrollment should be active |

It has been clear since plan offerings were posted for the ACA marketplace’s second Open Enrollment Period (OEP) in fall 2014 that “auto re-enrollment” can be dangerous for enrollees.

If marketplace enrollees take no action during OEP — declining to log on and update their income and other information relevant to subsidy eligibility and subsidy size, and review available plans — HealthCare.gov or the relevant state-based marketplace will auto-enroll them in their prior year plans, tapping the IRS and other data sources to update income and other personal information. If that plan is no longer offered, the marketplace will “crosswalk” the enrollee into the nearest equivalent, e.g., a plan by the same insurer in the same metal level. If the marketplace determines that the enrollee is no longer subsidy eligible, it will enroll her with no subsidy, exposing her to hundreds of dollars per month in premiums (one month, if she fails to pay any premium in the new plan year). Disenrollment occurs only if the person logs on and initiates it — or fails to pay the monthly premium when the new plan year begins.

Even when the enrollee’s income and family composition are essentially unchanged, remaining in last year’s plan (or a substitute into which one is crosswalked) without examining this year’s options can lead to major new expense. The plan’s premium may rise significantly. Worse, if another insurer (often a new entrant into the local market) undersells last year’s benchmark plan — the second cheapest plan, against which subsides are set — subsidies may shrink, hitting an enrollee who stays in a plan with a rising premium with a double whammy. The media was full of such stories in the fall of 2014. I told one myself, about a family of 3 in Philadelphia whose premium for a silver plan would have gone from $0 to $196 per month if a navigator hadn’t provided guidance.

The problem is not new, and it hasn’t gotten any better. In fact it’s gotten worse, as narrow-network HMO plans have become prevalent at the lowest price points, and cut-rate new entrants sometime render plans with more robust networks more expensive.. Another aspect of the problem is also not new, but when when it was brought to my attention this week it rather shocked me, and it may have major policy implications.

In SBMs, auto re-enrollment rules

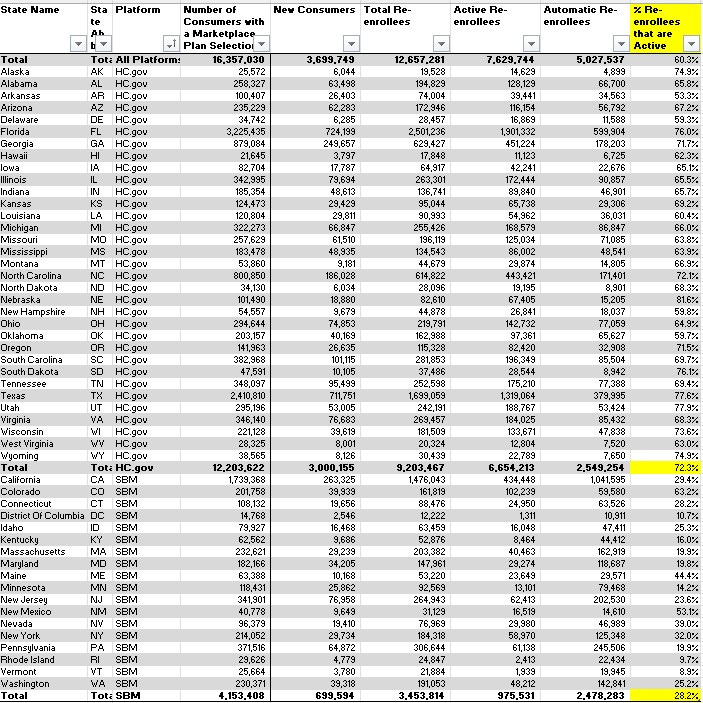

It’s this: According to CMS enrollment data, with one or two exceptions, the rate of passive renewal — autorenewal — is far higher in state-based marketplaces (SBMs) than in states using the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov. At present there are 18 SBMs (including D.C.) and 33 states using HealthCare.gov. In 2023, 72% of renewals in HealthCare.gov states were classified as Active — that is, the enrollee logged in, updated information as necessary, and re-applied, regardless of whether the enrollee switched plans. In SBM states, just 28% of renewals were classified as Active. Only two SBM states, Colorado and New Mexico, had active renewal rates above 50%.

In the table below, I added the column on the far right to the “By Enrollment Status” table in CMS’s State-level Public Use File for 2023. HealthCare.gov states are listed first, followed by SBMs.

Percentage of Re-enrollees who Actively Re-enroll, HealthCare.gov vs. SBMs, 2023

Again, this split is not new. In 2016, in the 37 states then using HealthCare.gov, 71% of re-enrollments were active, vs. 37% in 14 SBM states.

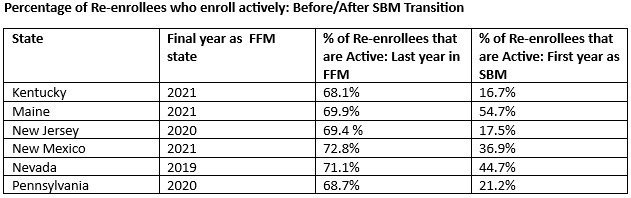

Since plan year 2020, six states have transitioned from HealthCare.gov to an SBM. Statistically at least, active reenrollment fell off a cliff every time.

Source: CMS State-level Public Use Files, 2019-2022

Given the high level of volatility in benchmark plans from year to year, and so in premium subsidies and net-of-subsidy premiums for any given plan, a high rate of autoenrollment is unquestionably a bad thing. The gap in active re-enrollment rates between HealthCare.gov states and SBMs is frankly astonishing, not least because it’s been hiding in plain sight since OEP for 2015 (I’m sure many people are aware of it, but several deeply experienced market watchers I contacted were not). If the gap is not an artifact of different record-keeping practices between the SBMs and the federal exchange, it should give states planning or considering an SBM transition serious pause. Six states have transitioned since 2020; Virginia is on track to do so next year; and states including Georgia (via waiver proposal), Texas (via legislation) and Oregon (in discussion stage) are considering a transition to an SBM.

Statistical anomaly?

My first thought, staring at the numbers in the first table above, was that the difference in active reenrollment states must be at least in part a statistical illusion. Perhaps SBMs track or classify their re-enrollees differently? Among “active” re-enrollees, CMS tracks how many switch plans — but only in HealthCare.gov states. In 2023, 42% of active re-enrollees in HealthCare.gov states remained in the same plan or a crosswalked plan. Perhaps, I thought, some or all SBMs only count those who switch plans as active re-enrollees.

No. Covered California, which accounts for 42% of enrollment in SBM states, told me in a statement that “Covered California reports considers an active renewal to be one in which the consumer (or an agent or navigator or other certified enroller on their behalf) logged into the application portal and updated their application and re-applied for the new year (which may or may not have included a change or update to income, etc.). We count all of these as active renewals, regardless of plan switching, in our data that is given to CMS.” A CMS spokesperson affirmed that the same is true for SBMs generally:

The definition of auto re-enrollment is the same between states using HealthCare.gov and states with State-based Marketplaces (SBMs). In both cases, consumers who actively make a plan selection in their previous year’s plan or their crosswalked plan are counted as active re-enrollees. Different outreach and operational strategies may explain some of the difference in the auto re-enrollment percentages between HealthCare.gov and SBMs.

I’m still not entirely convinced that reporting differences don’t have something to do with the active re-enrollment gap — perhaps particularly in transitional years. In particular, New Mexico’s active re-enrollment rates — 72.7% in 2021, its last year in the FFM; 36.9% in 2022; 53.1% in 2023 — seem anomalous. In 2022, New Mexico radically changed pricing structure in its marketplace, ensuring that gold plans were priced well below silver plans (silver plans have higher actuarial value for most enrollees, because of Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies). The resulting radical shift in metal level selection — gold selection rose from 26% to 58%, bronze plunged from 39% to 15% year-over-year — appears unlikely if almost half of the state’s enrollees (21,000 out of 46,000) were auto-re-enrolled.

Annually, too, CMS warns, in FAQs for the marketplace Public Use Files: “CMS does not fully validate application and enrollment figures for SBMs using their own platforms, and caution should be used when making comparisons between states using their own platforms as definitions may vary. “

A tale of brokers and e-brokers?

That said, there appears to be at least some structural impediment to active renewal in SBM sites compared to HealthCare.gov. What could it be?

Two related possibilities come to mind: assistance by brokers, and the availability to brokers serving clients in HealthCare.gov states of commercial online exchanges that enable brokers to track their clients’ status and that also — at least in the case of the largest commercial online broker, HealthSherpa — simplify and speed the enrollment process. Commercial online brokers have been fostered by CMS in a program first known as Direct Enrollment and, since 2018 as Enhanced Direct Enrollment (EDE), technology that enables an application submitted on an EDE site to be fully processed, subsidy included, without the enrollee (or broker) appearing to leave the site.

According to a KFF survey, 55% of brokers selling in HealthCare.gov states in 2022 said they never initiate applications on HealthCare.gov. 72% of brokers said they use private websites at least some of the time. In 2023, HealthSherpa alone accounted for 35% of enrollment in HealthCare.gov states — not counting auto-reenrollments, for which the e-brokerage is not credited. (Individuals as well as brokers can use HealthSherpa. The majority of enrollments through the platform are via brokers.) According to a Trump-era CMS brief, in Plan Year 2020 “nearly half” of enrollments in HealthCare.gov states were broker assisted, and the percentage had been increasing steadily for years (the Trump administration actively promoted brokers and disparaged government-funded nonprofit enrollment assistance).

It would help to be able to determine whether HealthCare.gov states rely more heavily on brokers than SBM states. One large data point suggesting not: California came early to reliance on brokers, and its 2023 enrollment profile (available here) reports that 56% of enrollees were assisted by a certified agent. Another: In Colorado, 55% of enrollees in 2023 were broker-assisted. In Pennsylvania, Pennie, the SBM launched in 2021, worked to increase broker participation in advance of the 2022 plan year, and did in fact boost the percentage of broker-assisted enrollments for 30% in 2021 to 40% in 2022.

In a January 2021 data brief, CMS claimed that EDE, the use of which had grown rapidly in the just-finished OEP, was increasing the rate of active plan selection among returning enrollees. The brief cited an overall increase in active reenrollment from 71% in OEP 2020 to 73% in OEP 2021. That said, active reenrollment rates have barely budged in states using HealthCare.gov since 2016, the first year that re-enrollment type was tracked. What’s consistent is the precipitous drop in active re-enrollment (or at least in recorded active enrollment) in states that transition to an SBM.

While EDE has only been operative since 2018, its predecessor, Direct Enrollment (DE), which did require a detour to HealthCare.gov to process a subsidy before sending the application back to the DE site, has been around since 2014. It may be that DE/EDE has facilitated active enrollment from the beginning, perhaps in part by giving brokers tools to push it. Then again, DE/EDE use has grown rapidly in recent years — HealthSherpa processed more than half of HealthCare.gov enrollments in 2023, excluding auto re-enrollments, for which EDEs get no credit — but active re-enrollment rates in HealthCare.gov have barely budged.

Early auto-renewal as deterrent to active selection?

I’ll float one more possible cause of the active re-enrollment gap based on my own experience in GetCoveredNJ, New Jersey’s SBMs, through which my wife and I first enrolled in coverage in mid-2022 and renewed for the first time this past November (for 2023). When I logged on in early November, I was somewhat nonplussed to find that I had been auto-enrolled in my 2022 plan. GetCoveredNJ does this prior to open enrollment. So do several other SBMs, and I believe all the SBMs auto-renew before HealthCare.gov does (I saw a chart of the auto-enrollment schedules recently but damn it, can’t find it). Breaking into an apparently completed enrollment and enrolling anew required overcoming at least a blip of internal resistance — was I cancelling my current coverage? Perhaps early auto re-enrollment discourages at least some active re-enrollment.

One hint in this regard: Pennie’s 2021 annual report, which encompasses OEP for 2022, addresses autoenrollment practice:

Pennie updated the renewal process for both passive and active customers, including implementing the auto-renewal process earlier than in the previous year. Pennie automatically renewed 99.6 percent of all qualified 2021 customers into 2022 plans, an increase from the 97 percent auto-renewal success rate for Open Enrollment 2021. Active shopping was promoted as an important step in the renewal process and for evaluating year-over-year plan changes, which resulted in a 61 percent increase in 2022 with 89,890 active renewals [29%] compared to 55,699 in 2021.

OEP for 2022 was the first OEP in which the premium subsidy boosts created by the American Rescue Plan Act were in effect, and that dramatic change in marketplace offerings may have driven the spike in active enrollment. In 2023, active renewals in Pennie dropped back to 61,138 (20%).

How much messaging through the medium?

Tara Straw, a senior policy advisor at Manatt Health, who while at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities in 2021 provided training to enrollment assisters about the intricacies and pitfalls of auto re-enrollment, suggested to me in an email that the exchanges’ communication with enrollees could be a factor in the active re-enrollment gap. She asked, with respect to my own experience with GetCoveredNJ, “Did you receive the volume of communication that HC.gov unleashes?”

The answer to that is an emphatic no. I created a login at HealthCare.gov back in 2014, and throughout every Open Enrollment Period the federal exchange still sends me messages urging me to enroll — 93 messages in OEP for 2023, to be exact. Those messages were about getting first coverage, not actively re-enrolling, but the volume gives some idea of the intensity of HealthCare.gov email communication.

From GetCoveredNJ last fall, prior to completing an application in late November for coverage this year, I received three emails urging me to get coverage (and several more after I had enrolled in a plan). I had been auto re-enrolled on October 7.

Count my experience as anecdotal support for a “hypothesis” that Tara Straw suggested as a possible partial explanation for the active re-enrollment gap: “that SBMs don’t message about shopping the way the FFM does and, even if they do, don’t do it with the frequency and aggressiveness as healthcare.gov.” That may well be the strongest hypothesis offered here, and bears further investigation.

To SBM or not to SBM?

The ACA’s creators intended and assumed that all states or almost all states would establish their own exchanges. Dead-end resistance to ACA enactment in Republican-run states precluded that, and the ACA marketplace kicked off in 2014 with 35 states relying on the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov. Way back in June 2014 Raymond Scheppach, a longtime director of the National Governors Association, predicted to me that most states would eventually opt to form their own exchanges, as states would want to integrate Medicaid/marketplace enrollment and exert control in various ways. Trump administration hostility to the marketplace — expressed most markedly in cutting Open Enrollment Periods and gutting financing for the ACA navigator program in HealthCare.gov states — convinced many blue state governments that they needed to insulate themselves from future Republican administrative assaults. SBMs also enable state variations such as wraparound subsidies. Republican administrations in Georgia and Texas have begun to toy with the idea of applying premium subsidies to ACA-noncompliant plans, an “innovation concept” floated by Seema Verma, CMS administrator in the Trump administration.

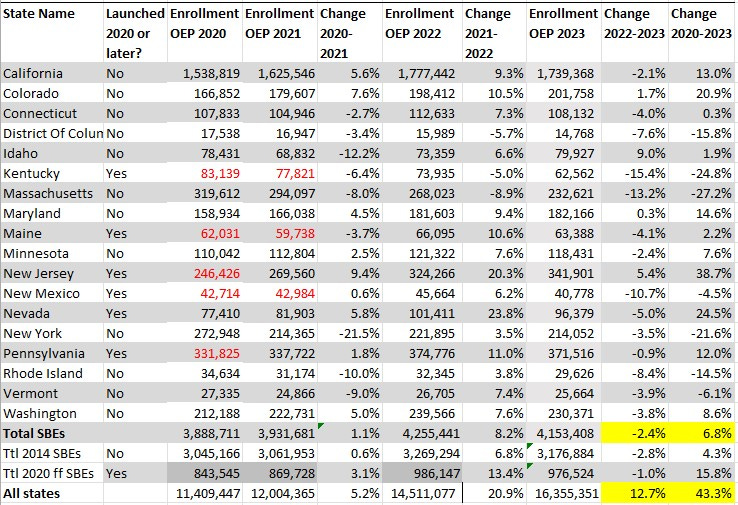

But SBMs have possible downsides that state governors and legislatures should consider before leaping. Enrollment growth since 2020 in the SBMs has seriously lagged growth in HealthCare.gov states, in fact turning negative in 2023, while enrollment in HealthCare.gov states increased by 19% this year. Most enrollment growth in HealthCare.gov was in the 12 states that have not yet enacted the ACA Medicaid expansion, as adults in those states with incomes in the 100-138% FPL range, who would be eligible for Medicaid in expansion states, can get free marketplace coverage. But enrollment growth in 21 expansion states using HealthCare.gov increased 10% in 2023, while enrollment fell by 2% in the SBMs.

Enrollment in Current State-based Marketplaces, 2020-2023

Source: CMS Marketplace Open Enrollment Public Use FilesTotals marked in red denote that the state was using HealthCare.gov in that year.

There may be good reasons for the lagging enrollment growth in SBM states, examined in some detail in this post. SBM states have relatively low uninsured rates, and in the years prior to the pandemic had better takeup rates than expansion states using HealthCare.gov. In 2022, unemployment dropped more sharply (albeit from higher levels) in the SBM states than in HealthCare.gov states, taking more potential enrollees out of the market. But while slower enrollment growth in the SBMs in recent years may be more attributable to the pool of potential enrollees than to takeup by those who need the insurance, the numbers should still give state policymakers pause.

To that cautionary note, add the low active re-enrollment rates in SBMs, which dates to the marketplace’s first reenrollment season. The why remains a mystery. But unless the active re-enrollment gap can be shown to be a result of different data crunching practices, it seems to me to point to a major advantage of the federal marketplace.

Photo by Any Lane

No comments:

Post a Comment