Note: Free xpostfactoid subscription is available on Substack alone, though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

|

| Pandora...don't ignore her |

Picture yourself in a boat on a river, with tangerine trees, and a Republican party that grounds genuine fiscal conservatism (the kind that eschews multi-trillion-dollar tax cuts) in fact rather than in lies and fantasy. What might a compromise on extension of the enhanced premium subsidies in the ACA marketplace look like?

Stop presses: It might look like the bill put out by the Problem Solvers’ caucus today. (I mean ‘‘stop presses” literally, as I was sketching out my own compromise here when I came across the bill in question.)

The Healthcare Optimization Protection Extension (HOPE) Act (summary here, bill text here) was introduced today by Problem Solvers members Tom Suozzi (D-NY), Don Bacon (R-NE), Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ), and Jeff Hurd (R-CO). It addresses two legitimate concerns about the enhanced premiums subsidies (eAPTC) created by the American Rescue Plan Act and currently funded only through 2025: that they spend too much money subsidizing high-income enrollees (questionable, but not absurd), and that they opened an easy pathway to fraud (true, but only in concert with other factors that can be addressed to shut the fraud down).

The HOPE bill only lightly increases the premium burden at incomes over 600% of the Federal Poverty Level ($93,900 annually for an individual, $126,900 for a couple, $192,900 for a family of four). The subsidy “cliff” — the cap on eligibility — goes back in place, but rises from the pre-ARPA (and now pending) 400% FPL to 935% FPL. The new cliff will take a substantial bite from some pretty affluent individuals and families, as explored below, but the ranks of those affected are small.

To crack down on fraud, the bill puts the emphasis where it belongs: on requirements for brokers and the Field Marketing Organizations (FMOs) and lead generators (advertisers, working mainly through often-scummy online ads) who send them clients. At the low end of the subsidy schedule, it does not require minimum premiums for the millions who qualify for zero-premium coverage under the eAPTC subsidy schedule, relying on controls on brokers to prevent enrollments effectuated without the enrollee’s knowledge or consent. By one well-grounded estimate, minimum premiums would reduce enrollment by about 1 million (out of about 8 million zero-premium enrollees in 2025).

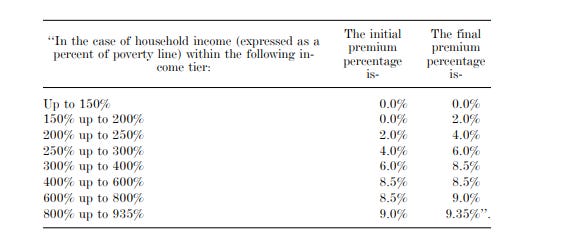

Here is the subsidy schedule the HOPE Act would create. It differs from the eAPTC status quo only in the percentages of income required for a benchmark silver plan at incomes over 600% FPL — and in reimposition of a subsidy cap at well over twice the income level of the pre-ARPA cap.

Some perspective on the subsidies upper end of the income scale: Before ARPA enhanced marketplace premium subsidies in March 2021, the plight of modestly affluent people who needed to rely on the individual market for health insurance but earned too much to qualify for subsidies was the ACA’s most potent political problem (though the inadequacy of subsidies for those who did qualify affected far more people). For perhaps 3-5 million people with income above the pre-ARPA income cap for subsidy eligibility (400% FPL, or $62,600/year for an individual, $128,600 for a family of four in 2026), the ACA’s market reforms (guaranteed issue, required Essential Health Benefits) made coverage very expensive, often prohibitively expensive. After this year’s 30% average spike in unsubsidized benchmark premiums, that unaffordability is all the more acute. The plight of the subsidy-ineligible belied the ACA’s promise of “affordable care” for all — and served for years as Republicans’ chief cudgel against the ACA. If the 400% FPL cliff is left in place, that cudgel will turn on Republicans.

The eAPTC created by ARPA removed the subsidy cap, instead capping premiums for a benchmark silver plan (the second cheapest silver plan in a given rating area) at 8.5% of income, regardless of income. 8.5% of your income is a lot for health insurance! At an annual income of $126,900 for a couple (600% FPL), that’s $10,787/year or $899/month (this and following premium quotes are derived from the KFF subsidy calculator, comparing pre- and post-ARPA enrollee premiums).

But if that sounds imposing, consider that the average unsubsidized benchmark premium for a pair of 62 year-olds in the marketplace in 2026 is $33,694/year, or $2,808/month —26.6% of income. Lowest-cost bronze for this couple would average$24,612/year, or $2,051/month, with a per-person deductible north of $7,000. That’s 19.4% of income. The full-year subsidy costs the federal government $22,907. The HOPE Act wouldn’t touch that subsidy. Should it? (For more graphic representation of the subsidy schedule’s effects, see Charles Gaba’s post.)

The subsidy haircut at 800% FPL ($169,200 for a couple), is 0.5% of income, as the enrollee’s share of the benchmark silver premium rises from 8.5% to 9.0% of income. That’s $846 a year, which is not going to break anyone at this income level. But again, there is a cliff at 935% FPL, or $146,328 for an individual and $197,753 for a couple. Returning to our 62 year-old couple, benchmark silver, at $33,694/year on average, will cost them 17% of income; lowest-cost bronze ($26,059/year), 12.4%. For a family of four, the 935% FPL subsidy cliff hits at $300,602/year. If the parents are both 55 years old, their premium for benchmark silver (if just over the cliff) would be $35,676 for the year.*

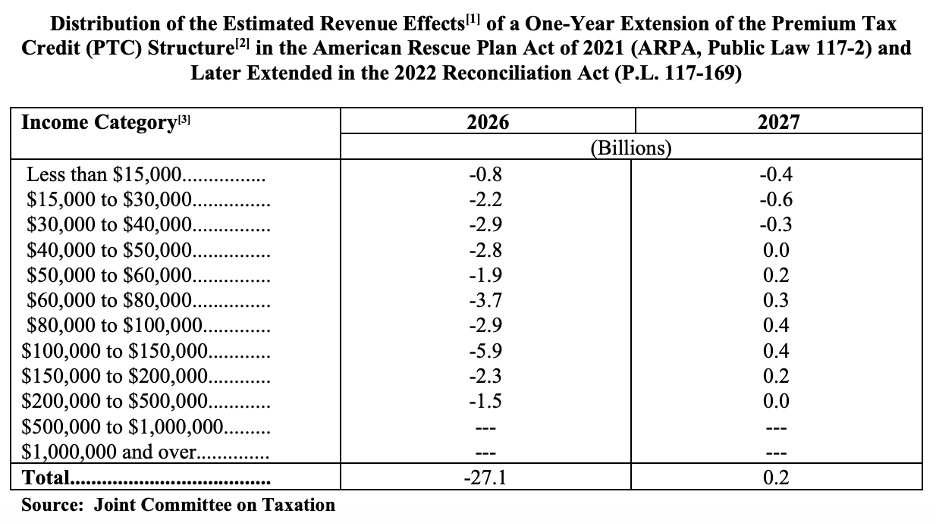

Neither the federal savings nor the suffering resulting from this 935% FPL cliff would be negligible. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that extending the enhanced subsidies for a year without any changes would cost the federal government $27.1 billion. Below, JCT breaks out the distribution of those costs by income (unfortunately, not by FPL).

Households with annual income over $150,000 FPL account for 14% of that $27 billion, or $3.78 billion. In the $150,000-$200,000 income range, however, only single-person households would go over the cliff, though some would take a relatively modest subsidy haircut. Households with income over $200,000, most but not all of whom would be over the cliff, account for 5.5% of the $27.1 billion cost of extending eAPTC in 2026. (The cost of a one-year extension would probably be less than estimated above, since the apparent expiration of eAPTC through most or all of Open Enrollment will inhibit enrollment.)

The bill also reproduces measures in the Insurance Fraud Accountability Act, introduced last March by Democrats Deborah Ross in the House and Ron Wyden in the Senate. These measures “impose criminal penalties for agents and brokers who engage in fraudulent practices, including enrolling individuals in plans without their consent and using deceptive marketing to target vulnerable groups” and “create a consent verification process, ensuring that individuals will be kept informed of any new enrollments or changes to their insurance coverage.” The HOPE Act also attempts to crack down on misleading advertising produced by lead generators and used by Field Marketing Organizations (FMOs) to send leads to brokers, holding brokers and FMOs accountable for any misleading materials they use, and requiring them to submit those materials to HHS for review and approval when requested. The HOPE Act also follows the IFAA in imposing “a requirement that individuals be able to access their account information on a website or other technology platform” other than the government-run exchange, i.e. in the Enhanced Direct Enrollment platform used by the broker, which is usually HealthSherpa. [Update: HealthSherpa, the dominant EDE platform, tells me that all enrollees already do automatically get a consumer account, both on HealthSherpa and on the federal exchange (HealthSherpa operates only on HealthCare.gov and on Georgia’s new SBM; no other SBMs allow EDE to execute enrollments).] The bill also imposes substantial penalties and possible criminal penalties on brokers who knowingly submit false information to the exchange.

Enrollment fraud has already been substantially curbed by a requirement that any agent or broker who newly takes on an existing account participate in a three-way call with the client and the exchange before gaining access to the account. That PITA for brokers has shaken out a lot of high-volume bad actors, or more likely, induced them to switch focus to other insurance products. Whether the further measures in the IFAA and the Hope Act would have a further positive effect, I don’t know. Importantly, though, they impose no new burdens on enrollees — as, for example, requiring minimum premiums or banning auto-reenrollment would.

Frankly, not to hurt its chances or anything (who’s listening anyway), the HOPE Act looks like a Democratic proposal, with a fig leaf for purple-district Republicans who want to get out from under a Sword of Damocles. It looks a lot like a compromise fantasy I was working on (picture yourself in a boat…) when I can across news of the bill. Below, just for fun, is the post I had in progress on, picking up the thread from the first paragraph above, which was drafted before I knew about the HOPE Act.

- - -

Prior post that was in progress: Let’s start by acknowledging that a marketplace of plans offered by (mostly) for-profit insurers paying negotiated rates to healthcare providers and offering an infinitely varied Swiss cheese of deductibles, coinsurance, copays and out-of-pocket maximums is a suboptimal way to cover those who lack access to other affordable insurance. A truly cost-effective program would have set provider rates at Medicare levels or some multiple (120%?) and required providers who accept Medicare to accept it.

That said, marketplace competition has favored cut-rate, narrow-network insurers who probably do pay well below commercial rates in the employer market. And thanks to the enhanced subsidies (let’s call them eAPTC, for enhanced Advanced Premium Tax Credits), the ACA’s marketplace has in recent years more or less fulfilled the function the ACA’s envisioned, increasing enrollment in the individual market by about 14 million since 2013 (from an estimated 10.6 million in 2013, the year immediately preceding the marketplace’s launch, to 24.3 million in 2025), in line with CBO’s original projections. And those plans in the reformed individual market are available to all who lack access to other insurance, regardless of medical condition, and provide coverage of Essential Health Benefits with annual caps on out-of-pocket expenses (albeit very high ones) and a ban on annual or lifetime coverage caps.

Current Republican proposals to “reform” the marketplace would make it worse. My last post provides a sampling, and Jonathan Cohn this week offered a deep dive into core decades-old Republican shibboleths: that higher out-of-pocket costs transform patients into smart shoppers, that tax-favored savings accounts will equip the masses for such smart shopping, that adding more risk and complexity to the market will improve it, that an individual market shaped by medical underwriting, which excludes and penalizes prospective enrollees for pre-existing conditions, is a lost Shangri-la. All of which is to say, that with regard to currently floating Republican and right-wing think tank “reform” plans, Sen. Brian Schatz is pitch-perfect:

“If they don’t have the votes, then what are we even doing here?…The burden is on them to demonstrate that they can help us enact something. I’m not super interested in six [Republicans] flopping around on the deck pretending they’re gonna save [Obamacare].”

Republican dreams of radically cutting premium subsidies and funding tax-favored accounts aside, fiscal probity allows for some reasonable marketplace reforms (real fiscal probity would replace the whole shebang with a program akin to traditional Medicare, paying Medicare rates or some multiple of them (120%?) to providers, and requiring providers that accept Medicare to accept patients in the new program). Reasonable reforms might include the following.

Trimming subsidies for high-income enrollees. Before the American Rescue Plan Act enhanced marketplace premium subsidies in March 2021, the plight of modestly affluent people who needed to rely on the individual market for health insurance but earned too much to qualify for subsidies was the ACA’s most potent political problem (though the inadequacy of subsidies for those who did qualify affected far more people). For perhaps 3-5 million people with income above the pre-ARPA income cap for subsidy eligibility (400% FPL, or $62,600/year for an individual, $128,600 for a family of four in 2026), the ACA’s market reforms (guaranteed issue, required Essential Health Benefits) made coverage very expensive, often prohibitively expensive.

ARPA removed the subsidy cap, instead capping premiums for a benchmark silver plan (the second cheapest silver plan in a given rating area) at 8.5% of income, regardless of income. 8.5% is a lot. At an annual income of $126,900 for a couple (600% FPL), that’s $10,787/year or $899/month. Sound like a lot? The average unsubsidized benchmark premium for a pair of 62 year-olds in the marketplace in 2026 is $33,694/year, or $2,808/month —26.6% of income. Lowest-cost bronze for this couple would average$24,612/year, or $2,051/month, with a per-person deductible north of $7,000. That’s 19.4% of income. The full-year subsidy costs the federal government $22,907.

I picked a near-elderly couple because that’s where the money is. Premiums rise with age, tripling from age 21 to age 64. For the near-elderly in particular, unsubsidized premiums are truly unaffordable, even at 600% FPL. Meaningfully trimming eAPTC eligibility at the high end without causing unacceptable hardship is tricky. [Here’s where I left off…]

—-

* While premiums in employer sponsored insurance remain higher than in the marketplace on average (generally, with lower out-of-pocket costs and more expansive provider networks), ESI premiums are not age-rated. The average family premium in the employer market this year is $$26,993, per KFF. In the marketplace, if the parents with two children cited above were 40 years old, the unsubsidized benchmark silver would cost them $23,960/year. Conversely, if they are subsidy-eligible, the older they are, the larger the bite the subsidy takes out of premiums for plans that cost less than the benchmark silver plan.

No comments:

Post a Comment