Note: Free xpostfactoid subscription is available on Substack alone, though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

|

| Does the NJ marketplace need a Huckabee-sting? |

The looming expiration of the enhanced Premium Tax Credits in the ACA marketplace (ePTC) increases the salience of the extent to which different states encourage or enforce strict “premium alignment,” A.K.A. silver loading, the pricing of the full value of Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) into silver plans.

Here, we’ll contrast current plan offerings in a state marketplace with some of the most extreme silver loading effects, Arkansas, with a state where the effects are among the weakest, New Jersey.

If you are unfamiliar with how silver loading works or why it exists, see the explanation at bottom.

To defend against the looming expiration of the enhanced ACA subsidies funded only through 2025, Arkansas implemented the nation’s strictest “premium alignment,” requiring insurers to price silver at 1.46 times what it would be priced at the baseline silver actuarial value of 70%. That is, Arkansas requires insurers to price silver plans as if all silver plan enrollees have income under 200% FPL and so obtain plans with actuarial value of 94% (the AV of CSR-enhanced silver for enrollees with income up to150% FPL) or 87% (silver AV for enrollees in the 150-200% FPL income bracket) — an average AV of 91%. For a convoluted tale of how Arkansas arrived at this point, see Charles Gaba.

Pricing silver as if all enrollees have income under 200% FPL is meant to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. A “CSR factor” like Arkansas’ ensures that gold plans will be cheaper than silver plans with the same provider network, making silver plans an illogical choice for enrollees with income over 200% FPL, since gold plans have a higher AV than silver for enrollees above that income threshold. That assumption has been borne out in the Texas marketplace, where in 2025, just 1% of the state’s 1.9 million silver plan enrollees had income over 200% FPL.* In 2025, 78% of silver plan enrollees in Arkansas obtained 94% AV or 87% AV. The average weighted AV for silver plan enrollees in the state was 86.8%. It’s not a great leap to assume average silver plan AV of 91% under the current pricing regime.

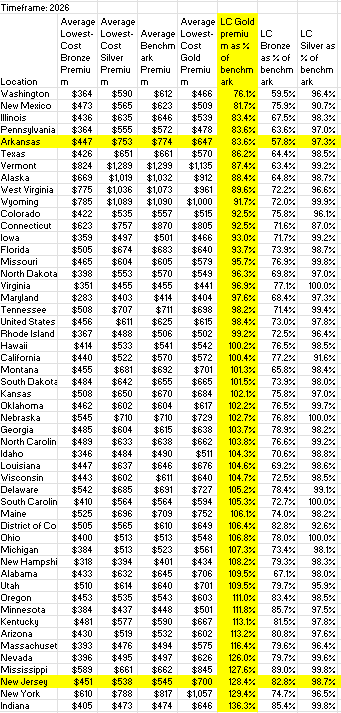

Thanks to this pricing formula for silver plans, Arkansas has the nation’s widest premium spread between the average lowest-cost bronze plan and the average benchmark (second cheapest) silver plan. On average, the premium for the lowest-cost bronze plan in Arkansas is just 57.8% of the benchmark silver premium. Gold coverage in Arkansas is also very cheap, averaging just 83.6% of the benchmark. On that front, Arkansas is tied with Pennsylvania for fourth-lowest in the nation.

New Jersey, on the other hand, has anomalously low-priced silver plans (relative to bronze and gold) and the highest percentage of silver selection in the nation, at 83.3%. That has been good for enrollees with income up to 200% FPL, as silver is roughly platinum-equivalent below that income threshold, and it’s worked well in the enhanced-subsidy era, when the state’s supplemental subsidies have made silver coverage available for free or close to free at incomes up to 200% FPL. New Jersey also has relatively low, semi-standardized deductibles, and major insurers have relatively robust networks. So it’s been a pretty good marketplace in the enhanced subsidy era, and enrollment more than doubled from OEP 2021 to OEP 2025.

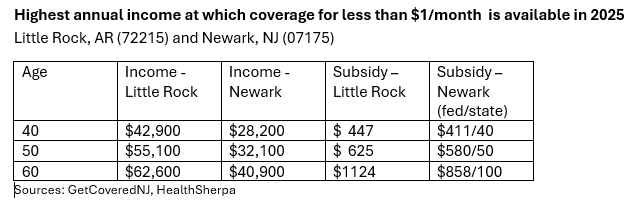

But relatively underpriced silver and massively overpriced gold is problematic in a post-ePTC era. In New Jersey, the premium spreads between benchmark silver and lowest-cost bronze are the seventh narrowest in the country: the premium for lowest-cost bronze in New Jersey averages 82.8% of the benchmark silver premium, compared to just 57.8% in Arkansas. As a result, notwithstanding New Jersey’s supplemental state premium subsidies, which range from $20 to $100 per month for a single person, rising with income, near-zero-premium coverage is much less widely available than in Arkansas, as illustrated below. (In Arkansas, absolute zero-premium coverage does not exist, though premiums can be as low as 4 cents per month. Accordingly, I’ve flagged the highest income at which bronze coverage is available for less than $1/month.)

While the wide availability of zero-premium (or near-zero-premium) bronze coverage in states like Arkansas is likely to limit coverage losses as ePTC expires, it is something of a mixed blessing for enrollees with income under 200% FPL (e.g., most enrollees, especially in low-income states like Arkansas). The difference in out-of-pocket exposure for enrollees with income up to 200% FPL between bronze plans (60% AV) and silver plans (94% or 87% AV) is vast. In 2026, the average bronze deductible in plans where there is no separate drug deductible is $7,476, compared to $80 for silver plans at incomes up to 150% FPL and $790 for silver plans at income in the 150-200% FPL range (KFF). Gold plans also have considerably higher out-of-pocket exposure than silver plans at incomes up to 200% FPL. Silver selection at incomes up to 200% FPL has been eroding since 2017; this year, it will doubtless erode further. Still, bronze coverage is better than no coverage, even at the lowest incomes.

The New Jersey marketplace also suffers from gold plans priced so high they are effectively unaffordable. In 2025, just 1.2% of New Jersey enrollees selected gold plans, compared to 35% in Texas — and 56% of Texas enrollees who reported income over 200% FPL (460,000 out of 819,00).

Here is a snapshot comparison of lowest-cost bronze and gold and benchmark silver options for an individual earning $40,000 (256% FPL) at ages 40 and 60 in Little Rock and Newark:

New Jersey almost forces many enrollees into silver plans, as the 83% silver selection in the state illustrates.

Since 2023, a New Jersey bill (currently S. 1971) that would put the state marketplace on a two-year path to strict "premium alignment" has been hanging fire. The bill, sponsored by Senate Health Committee Chair Joseph Vitale, would require that insurers price silver plans in proportion to the average actuarial value held by all silver plan holders in year 1, and to price silver at an assumed AV of 90% in year 2. The bill would radically reshape the choice architecture in the state marketplace, and at least one major insurer has claimed that its plans with their current network tiering could not be priced according to the bill’s mandated formula. Some negotiation may be in order, and possibly some retooling of the state’s standards for plan design at each metal level. But the extreme bias toward silver plans in the state is likely to hurt enrollment if ePTC is not renewed.

Update, 12/29: Benjamin Hardy of the Arkansas Times, who took a deep dive into the Arkansas Insurance Department's interactions with Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders as it implemented strict silver loading, more recently spotlighted gold plan alternatives available to subsidy-eligible Arkansas enrollees in 2026. Re the current enrollment season, Hardy writes in an email:

Though they did a great job implementing premium alignment, state officials have done a horrible job getting the word out about this. So have the insurance companies. When I was initially reporting my story, the reaction from most people I talked to — consumers, advocates, even some insurance agents and brokers — was confusion and bewilderment that Gold plans would cost less than Silver. Some argued with me and told me I was wrong. Meanwhile, people on Silver plans (most people) have been getting notices in the mail telling them their premiums are about to double or triple in cost. Those notices included no information telling them that a cheaper, better option was likely available, just a generic "go shop around" message that's easily ignored. As you know, most marketplace enrollees don't shop, they just reenroll in their current plan. I feel sure that some percentage of them this year will simply drop without ever looking on Healthcare.gov.

P.S. I’ve corrected a slip on the abbreviation for Arkansas above (AR, not AK).

- - -

Note: What is silver loading? The ACA statute stipulates that the federal government reimburse insurers separately for the value of Cost Sharing Reduction, a secondary benefit that attaches only to silver plans in the ACA marketplace and only for enrollees with income up to 250% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). That has not happened since 2017; instead, the value of CSR is priced into premiums — usually into silver plans only, at least theoretically, but in practice to varying degrees.

The switch originated with Trump, in a so-far-final round of partisan conflict over the ACA statute. The ACA’s drafters neglected to make funding for CSR mandatory, and the Republican Congress refused to fund it. Through 2016, the Obama administration found the necessary funds in couch cushions, and the Republican House sued in 2014 to stop the payments. A judge upheld the suit but stayed the ruling pending appeal. When Trump was elected, it was widely anticipated that he would cut off the payments. In October 2017, following the final death knell for legislative ACA repeal, he did so — abruptly, not only ending reimbursement for the upcoming 2018 plan year, but stiffing insurers for the last three months of 2017. He then crowed that he’d killed Obamacare.

Ironically, the likely effects of cutting off CSR reimbursement were by that point long understood, and insurers and state regulators were prepared (though time was short to adjust for the 2018 coverage year, with open enrollment for 2018 just two weeks away). Regulators in almost all states allowed or encouraged insurers to price CSR into silver plans only, inflating silver premiums and therefore premium subsidies, which are set so that enrollees pay a fixed percentage of income (on a sliding scale) for the benchmark second cheapest silver plan. Inflated benchmark premiums widened spreads between the benchmark and cheaper plans, rendering bronze plans free for millions of enrollees. Moreover, the CSR value now loaded into silver premiums makes silver plans roughly equivalent to platinum plans for enrollees with income up to 200% FPL — the vast majority of silver plan enrollees. When fully implemented, “silver loading” — pricing silver plans in accord with the average actuarial value obtained by silver plan enrollees — makes silver plans more expensive than gold plans. This dynamic was first laid out in an HHS ASPE brief in December 2015, followed by an Urban Institute analysis in January 2016 and a CBO analysis in August 2017.

As it turned out, “silver loading” —pricing the full value of CSR into silver plans — never really took full effect in most states, as insurers continue to underprice silver plans. That’s apparently because a) they compete to offer lowest-cost and benchmark silver, still the dominant metal level; b) low-income enrollees in plans with strong CSR utilize medical care less than anticipated, inhibited by relatively low but still substantial out-of-pocket costs; and c) the ACA’s risk adjustment formula doesn’t reflect this low utilization and thus tends to penalize insurers who sell a lot of bronze or gold plans. In 20 states, however, average gold premiums are lower than average benchmark silver premiums, some because of state regulatory or legislative requirements, and some by insurers’ choices. And in all states, silver loading has generated significantly lower-cost bronze plans and at least somewhat lower-cost gold plans, net of subsidy, than would be the case were CSR still reimbursed separately. In 2018, KFF estimated that 4.2 million uninsured people were eligible for a free bronze plan. As a result, according to an estimate by Aviva Aron-Dine (linked to by Levitt above), the CSR cutoff boosted enrollment by about 5% by 2019.

About ten states (including Texas) now effectively require marketplace insurers to price silver plans either in strict accord with the average actuarial value obtained by silver plan enrollees (thanks to CSR, the majority in most states are in plans with 94% or 87% AV) or, more radically, under the assumption that all silver plan enrollees have income under 200% FPL and therefore obtain AV of 94% or 87%. The latter (pioneered by New Mexico) is meant to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, since this assumption prices gold plans (80% AV) well below silver, so no one who’s not eligible for the two highest levels of CSR has any reason to choose silver. In advance of Plan Year 2026, Arkansas, Illinois and Washington implemented strict “premium alignment” of this kind.

—

* All enrollment statistics cited above are derived from CMS’s 2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Public Use Files. The state price spreads from the benchmark are derived from this KFF table. (I added columns dividing average premiums for lowest-cost bronze and gold plans by the average benchmark premiums. Snapshots are at bottom.) Plan pricing in Little Rock and Newark at different incomes and ages is drawn from the e-broker HealthSherpa for Little Rock and GetCoveredNJ for Newark (as HealthSherpa does not incorporate state supplemental subsidies). I use the HealthSherpa plan shopper rather than HealthCare.gov’s because on HealthSherpa you can edit just one factor — zip code or age or income — and get instantly adjusted results. Try it!

Here is the KFF data on plan pricing by metal level, sorted lowest-to-highest for lowest-cost bronze and lowest-cost gold relative to the benchmark. The three columns on the right are my addition.

No comments:

Post a Comment