Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

Providing ideological cover for Republicans who seek to cut hundreds of billions of dollars out of federal Medicaid funding, the Wall Street Journal editorial board would have you believe that federal Medicaid spending is out of control, that rich states get more than their fair share of federal Medicaid funding, that cuts to the projected spending growth rate under current law are not cuts, and that Medicaid isn’t much worth having anyway. That’s all false of course.

Let’s look at these nostrums one by one.

Undue spending in Medicaid growth. The WSJ editorialists write:

Medicaid spending as a share of federal outlays rose to 10% from 7% between 2007 and 2023, while the share of Social Security and Medicare remained stable.

Well yes, of course. The ACA Medicaid expansion, rendered optional by the Supreme Court in 2012, offered Medicaid eligibility to all lawfully present U.S. adults with income up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level, excepting those subject to a federal 5-year bar on new immigrants. As of the program’s full launch in 2014, 24 states had enacted the expansion, and as of now, 40 states plus D.C. have done so. Medicaid enrollment has accordingly grown by 38% since 2013 (and had swelled even higher as of 2023, the year cited by the Journal, as a result of the pandemic-induced three-year moratorium on disenrollments. Medicaid enrollment has dropped 17% since the 2023 peak.)

Democratic states grab more than their fair share of federal largesse. We are asked to believe:

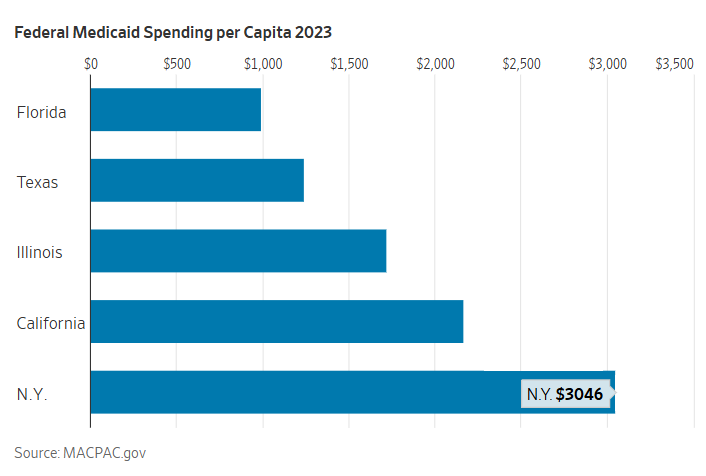

Democratic-run states receive disproportionately more federal Medicaid dollars. New York received $3,046 for each state resident in 2023 based on the most recent federal data. Federal Medicaid dollars also subsidize California ($2,167 per resident) and Illinois ($1,715) much more than Florida ($991) and Texas ($1,239).

Now this one is just silly. Blue states receive more “per resident” because they enacted the ACA Medicaid expansion and thereby enrolled a far larger proportion of their population than the dwindling set of “nonexpansion” states that have chosen instead to keep their uninsured rate at double that of peer expansion states. Kentucky, with a population of 4.6 million, drew $13.5 billion in federal Medicaid dollars in 2023 — about $2,800 per resident. Arizona, population 7.6 million, received $18.1 billion in federal Medicaid funding in 2023 — $2,500 per resident, more than New York.

While the 90% FMAP for the ACA expansion population closes the funding gap somewhat between rich states and poor states — the latter have a higher FMAP for all other Medicaid enrollment categories — the rich and blue states don’t receive a disproportionate amount of federal dollars. Some, notably New York, do have higher per-enrollee costs than the national average —as do some low-income states, including Mississippi, the state with the lowest per capita income.

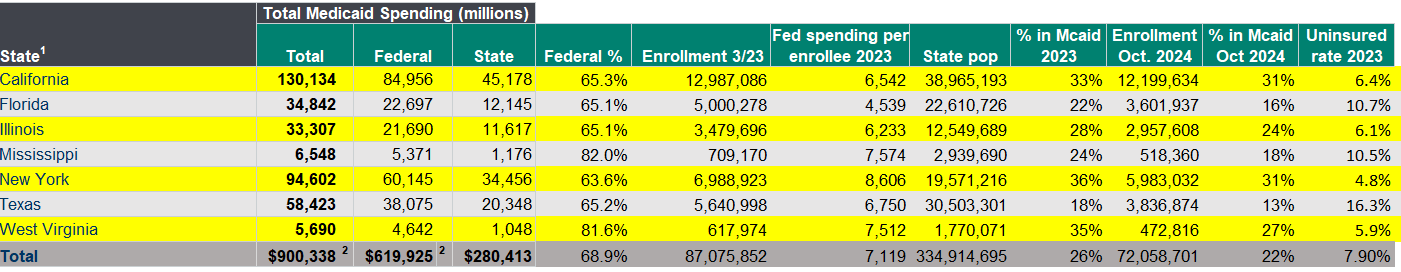

The table below shows federal dollars per enrollee for the states cited by the WSJ above, along with West Virginia, a low-income state that has expanded Medicaid, and Mississippi, a low-income state that hasn’t. As enrollment was inflated by the pandemic moratorium in 2023, I’ve included totals from March 2023 and also October 2024, the last month available, to add perspective. Also shown are the percentage of the state population covered by Medicaid and the state uninsured rate in 2023, the last year available. CHIP enrollment is not included, as MEDPAC does not include CHIP in the spending table on which I’ve built (sources at bottom).

States that have accepted the ACA Medicaid expansion are marked in yellow.

Medicaid Spending and Enrollment in Select States, 2023 and 2024, with Uninsured Rate

Sources:

Federal/state Medicaid spending: MACPAC

Population by state: Census Bureau

Medicaid enrollment (3/23 and 10/24): CMS Monthly Reports

Uninsured rate: KFF

Note that the the percentage of the total population in Medicaid in the expansion states is roughly double that of the nonexpansion states, while the uninsured rate is roughly double in the nonexpansion states. Note also that while spending per enrollee is very low in Florida and very high in New York, it’s not particularly low in Texas (which enrolls so few people that many must be in acute need) or particularly high in California or Illinois. The cost of care varies considerably in different regions of the country, as does the mix of Medicaid enrollees and the benefits offered.

Silly as it is, the WSJ’s per-resident spending measure also ignores the fact that Florida and Texas have partially compensated for their refusal to expand Medicaid with rapid enrollment growth at low incomes in the ACA private-plan marketplace. In 2024, Florida, population 23.3 million, had an average of about 4 million subsidized marketplace enrollees per month* receiving an average premium subsidy of $568 per month, while California, population 39.4 million, had about 1.6 million average monthly subsidized enrollees receiving an average of $526 per month. That is, “per resident,” Florida collected about $1,173 in federal subsidies, while California drew about $250.

Cuts are not cuts. The WSJ editorialists claims that the $880 billion Republicans might cut from CBO’s 10-year projections of Medicaid spending is not a cut because spending would grow in absolute dollar terms. That’s also silly — a perpetual Republican talking point to justify savage proposed cuts. Population grows, inflation is inevitable, and medical inflation usually exceeds overall inflation — though per-enrollee spending growth in Medicaid has been far slower over time than in any other type of U.S. health coverage. Oh, and emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic happen — and will all but certainly happen again. Thanks mainly to Medicaid, the uninsured rate barely budged when 20 million people lost their jobs in spring 2020, while Medicaid enrollment soared by some 20 million before falling back during the unwinding of 2023-24. Per capita caps on the federal Medicaid contribution, the largest single Medicaid cut on the Republican menu (though disavowed for the moment by Johnson), would strangle the program over time.

While flawed and chronically underfunded, Medicaid is a major contributor to the national welfare. Consider:

Medicaid controls costs: From 2008-2023, per-enrollee spending grew by 80.4% in private insurance, 50.3% in Medicare, and 30.3% in Medicaid, according to a KFF analysis of National Health Expenditure data.

The federal contribution is higher for low-income than high-income states: in fact, the federal matching rate (FMAP) varies directly according to state per capita income. For FY 2026, FMAPs range from 76.9% for Mississippi to 50% for California, New York and other wealthy states. While wealthy states generally benefit from the 90% FMAP for the ACA Medicaid expansions, so do many low-income states (40 stats plus D.C. have expanded Medicaid to date).

The ACA Medicaid expansion cut the uninsured rate nationally by about 40%. From July 2013 to October 2024, Medicaid enrollment increased by almost 23 million. From 2013 to 2023, the national uninsured rate dropped from 14.6% to 7.9%, chiefly as a result of the expansion.

Medicaid enrollees are slightly more satisfied with their coverage than enrollees in employer-sponsored insurance, with 82% rating their coverage excellent or good according to a KFF survey.

To borrow a timely set of links from Matthew Yglesias: various studies show that Medicaid enrollment has “a meaningful impact on mortality, as well as long-term better economic outcomes for covered kids [see also here] and reductions in crime” — as well as a positive impact on employment among those with disabilities.

Since Trump blithely promised not to cut Medicaid while endorsing the Republican House budget resolution that requires at least $650-880 billion in cuts to the program, Republicans are tuning their guitars to claim that they’re not cutting benefits, only waste and fraud. The Paragon Institute will lead the charge with an array of misleading claims — e.g. that CMS’s accounting of the “improper payment rate” in Medicaid (which is lower than the rate in Medicare) can be construed as a measure of fraud, whereas it mostly flags inadequate documentation. More sophisticated ideological cover for cuts than the WSJ’s are forthcoming. I hope the good scholars at CBPP, the Georgetown Center for Children and Families, KFF, Brookings, CAP, and throughout academia are ready for the onslaught.

—-

* Average monthly enrollment figures for the ACA marketplace in 2024 are not yet published, so I used effectuated enrollment as of February. In 2023, average monthly enrollment exceeded February effectuated enrollment, pushed by the Medicaid unwinding, which was also in progress through about half of 2024.

Photo credit: Jan Gossaert, Cain Killing Abel, Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery

No comments:

Post a Comment