Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

|

| CMS administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure |

It’s a common complaint among Biden supporters that in the Biden years the mainstream media has tended to emphasize the dark side of economic news at a time when the U.S. economy is “the envy of the world,” as the Wall Street Journal recently put it — with economic growth double the rate of any other G7 economy, an unemployment rate that started at 6.3% in January 2021 and has now been under 4% for 27 consecutive months, wages up 4-5% in each of the last two years, and post-pandemic inflation well below the levels suffered in other wealthy countries.

Notwithstanding a historically robust economy, more than half of voters believe the economy is “poor,” according to the latest New York Times/Sienna poll, and they rate Trump better able to steer the economy than Biden by astonishing double-digit margins. In a Politico-Morning Consult poll conducted in late April, fewer than half of respondents said they knew “a lot” or “some” about the American Rescue Plan (which showered cash on individuals and families, states and businesses while the pandemic was in full force), the bipartisan infrastructure bill, or the CHIPS and Science Act, while a slight majority, 52% said they knew “a lot” or “some” about the Inflation Reduction Act. The Biden administration was instrumental in the shape and passage of all these bills, which together have sparked investment, building and manufacturing booms. The S&P 500 is up 39% since Biden took office on Jan. 20, 2021.

Media critics complain that coverage of economic conditions has been relentlessly negative, emphasizing inflation and the persistent (inherently perpetual) threat of a recession that hasn’t materialized. The tenor of Biden coverage is piquantly captured on a daily basis by Doug J. Balloon’s “New York Times Pitchbot” on Twitter, which daily or hourly proposes article themes such as

Fitting this category is the framing of a substantively solid and nuanced assessment of how healthcare might play in the presidential election by Axios’s Caitlin Owens, Health costs threaten to overshadow Biden's historic coverage gains

The opener:

President Biden has come closer than any of his Democratic predecessors to reaching the party's long-standing goal of universal health coverage, but unaffordable care costs may overshadow the achievement.

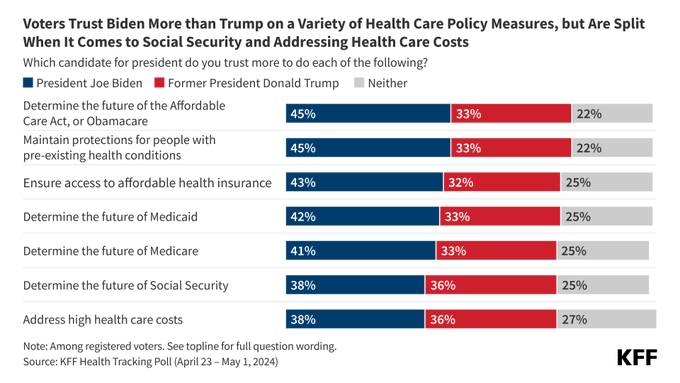

It is absolutely true that healthcare costs rise steadily, and rise faster than inflation, and cause widespread financial stress. It’s also true that Owens gives considerable space to the flip side: that the Biden administration has brought the uninsured rate below 8%; that healthcare costs have risen more slowly since the ACA passed than previously; that Democrats are running on policies that make care more affordable, e.g., extending the ARPA boosts to ACA premium subsidies and the IRA’s capping of insulin costs; and that healthcare is “still a good issue for Democrats” (i.e., voters trust Democrats more than Republicans to protect Medicare, Medicaid and the ACA).

But the framing, again, fits a dominant media pattern. Politics aside, in U.S. healthcare, things are always getting worse — and better. Corruption of medical care by the profit motive gets ever more intense, fueled by hospital system consolidation, vertical integration (by insurers and hospital systems), and private equity ownership. At the same time, some government measures have been effective as curbs, or are starting to be, or show future promise. Democrats and Biden have as strong a case as can reasonably be expected in U.S. politics for voter approval of their healthcare policies.

Let’s take a look at various programs and initiatives created by or altered by the Biden administration and Democrats (or in one case, passed in December 2020 with bipartisan support and implemented in January 2022) that have lowered healthcare costs for various constituencies.

ACA marketplace. It’s true that too many ACA marketplace enrollees are exposed to high out-of-pocket costs. In 2024, 8.6 million on-exchange enrollees, 40%, obtained plans with an actuarial value of 73% or lower — well below the average AV of employer-sponsored plan, which is around 84%. But the subsidy boosts created by the American Rescue Plan, which rendered benchmark silver plans with Cost Sharing Reduction free to enrollees with income up to 150% FPL, triggered a huge influx of low-income enrollees in states that have refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion, and most of those enrollees are in plans with 94% or 87% AV — better than the average employer-sponsored plan. In OEP 2024, 9.9 million marketplace enrollees are in plans with 94% or 87% AV, up from 5.3 million in OEP 2021. (Conversely, the proportion of low-income enrollees who obtain that high AV by selecting silver plans has dropped, as I have explored in several posts.)

No Surprises Act. This bill, passed with bipartisan support in December 2020 and enacted in January 2022, provides the greatest check on out-of-pocket costs that no one feels, because the bills not sent to patients would by definition have been surprises — bills from out-of-network providers working at in-network facilities. A survey by insurers (AHIP and BCBS) in early 2024 found that 10 million medical claims were subject to the law — that is, were out-of-network claims submitted to insurers — in the first nine months of 2023, and that the law was enabling insurers to expand their networks. Resolution of disputed OON claims between insurers and providers has been problematic, as conservative courts have struck down the arbitration rules established by HHS to resolve payment disputes between insurers and out-of-network providers, and arbitration awards to providers have been troublingly high. But consumers have been taken out of the equation, and a major scourge inflicting significant debt on a large number of Americans has been mostly removed (in a major exception, ground ambulance rides are not subject to the law). In 2020, according to an HHS brief (citing this KFF infographic), nearly 20 percent of insured adults in the two years prior received a surprise bill because the provider was OON, and two-thirds of adults worried about being able to afford unexpected medical bills. OON prevalence was more than 12% in emergency departments, according to Health Care Cost Institute data cited in the HHS brief.

Prior to NSA passage, patients who scheduled a procedure with an in-network provider were often billed by ancillary providers who were out-of-network — pathologists, anesthesiologists, assistant surgeons, and others. Emergency room patients at in-network hospitals had no way of knowing whether those who treated them were in-network — and many ERs, including every ER in some regions, were staffed entirely by outside practices, often private equity-owned mega-practices that might bill as high as 11 times Medicare rates. Healthcare reporters at Kaiser Health News, the New York Times, Vox and elsewhere spent years documenting egregious OON bills, such as a $117,000 bill from an assistant surgeon. In a real sense, surprise billing rendered virtually all commercial health insurance illusory, as out-of-network “balance bills” sent to patients were not subject to health plans’ out-of-pocket caps, so there was no limit on potential financial exposure. That particular form of patient abuse is mostly ended.

Medicaid: disenrollment moratorium and its “unwinding.” The pandemic emergency moratorium on Medicaid disenrollments enacted through the Families First Act in March 2020 was a major pandemic policy success, as it took effect just in advance of a short-term loss of 20 million jobs nationwide. Despite those job losses, the uninsured rate barely budged in the first years of the pandemic. Unfortunately, the “unwinding” of enrollment following the end of the moratorium in May 2023 has exposed all the dysfunction and in some cases cruelty of state Medicaid administration. In the year since the unwinding began, about 22 million people have been disenrolled from Medicaid, according to the KFF unwinding tracker — more than double the number who would be disenrolled in the course of a normal year, and more than 2/3 of them for “procedural reasons,” i.e. because enrollees did not receive renewal materials or did not fill them out. (An unknown but probably considerable portion of these disenrollees likely did not respond because they have obtained other insurance.) According to a March 2024 KFF survey, 23% of respondents disenrolled during the unwinding said they were uninsured at the time of response — which might suggest at least a short term increase in the uninsured population of 5-6 million. As of January, according to KFF tracking, the net Medicaid enrollment reduction (including the influx of new enrollees and re-enrollments of those wrongly disenrolled) was about 63% of the disenrolled total. If that ratio has held through May, total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment would now stand at about 80.2 million — down from 94 million in May 2023, but still up from 73.8 million in January 2021.

Medicaid: ACA expansion. Meanwhile, during the Biden years, four states that had refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion have enacted it: Oklahoma, Missouri, South Dakota and North Carolina. Those expansions have added about a million people to the Medicaid rolls. As of September 2023, 23.2 million people rendered eligible by ACA expansion criteria were enrolled in Medicaid, up from 18.7 million in 2020. The total is probably down considerably thanks to the unwinding. At the same time, North Carolina’s expansion, effective Dec. 1 of last year, has added 447,000 new enrollees.

Medicaid: 12-month postpartum eligibility. Via the American Rescue Plan, Democrats in the Biden years also smoothed the path for states to offer 12 months of postpartum coverage to women who had gained Medicaid through pregnancy, allowing states to make the change via State Plan Amendment (SPA) rather than the previously required Section 1115 waiver. The previous norm in many states was just two months of postpartum coverage. Extended postpartum coverage is a huge boon to maternal — and, by extension, infant — health. The SPA has a quicker application and approval process than a 1115 waiver and, unlike the waiver, does not have to be budget-neutral for the federal government. Originally in effect for 5 years, an omnibus budget bill passed at the end of 2023 made the 12-month SPA process permanent.

Since the federal government pays a higher percentage of the premium for adults rendered eligible for Medicaid via the ACA expansion (income up to 138% FPL) than for those rendered eligible for pregnancy (eligible up to a usually higher income threshold), Biden administration guidance also simplified the process by which a state could transition 12-month postpartum enrollees to the higher reimbursement rate (in effect allowing states to do this in bulk, calculating the proportion of enrollees with income under the 138% FPL threshold). To date, 47 states (including DC) have implemented 12-month postpartum enrollment; two more have SPAs in the works; Wisconsin has proposed a mere 90-day extension; and Arkansas is the sole holdout.

State initiatives reducing costs for ACA plans and equivalents. Also during the Biden years, enrollment has grown in three state programs that provide standardized coverage with low out-of-pocket costs to low income enrollees. New York’s Essential Plan, which provides coverage with actuarial value ranging from 92-99% (higher at lower incomes) at zero premium, now covers 1.4 million people, up from 883,000 in January 2021. New York opened the program at zero premium to enrollees in the 200-250% FPL income range in April, via a waiver approved by CMS; enrollment in that income bracket has more than doubled, from 62,000 in regular marketplace plans as of the end of OEP 2024 to 132,000 in the Essential Plan this month. For OEP 2024, Massachusetts extended eligibility for its high-AV, standardized benefit ConnectorCare program from 300% FPL to 500% FPL, and overall enrollment in the state (in ConnectorCare and regular QHPs) was up by 78,000 this year (fueled partly by the ConnectorCare expansion but probably mainly by the Medicaid unwinding). Enrollment in Minnesota’s BHP, MinnesotaCare, was up modestly this year. During the Biden years, too, California, Colorado, Connecticut and New Mexico have added state subsidies that enrollee reduce cost sharing, while Maryland, New Jersey and Washington have added state premium subsidies.

Medicare Part D revision. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August 2022, aims to reduce both federal and enrollee spending in several ways. Enrollees will not feel the effects of the most radical provision, Medicare negotiation of prices for select expensive and highly used drugs, until 2026, though the first ten drugs subject to price negotiation have been named. A second provision, requiring drugmakers to provide rebates for drugs whose prices increase above the inflation rate, went into effect in 2023, as did a $35/month cap on out-of-pocket spending for insulin and zero cost sharing for select vaccines.

A third provision, capping enrollees’ annual out-of-pocket costs, went into effect this year. The hard $2,000 cap that goes into effect in 2025 is better known than this year’s transitional cap, which ends enrollee payments during the so-called “catastrophic phase” of coverage — that is, after about $3,300 in out-of-pocket costs. Until 2024, enrollees paid 5% of the cost of the drugs they used in the catastrophic phase.

According to an HHS brief, in 2022, 1.5 million Part D enrollees who did not qualify for low income subsidies (LIS) reached the catastrophic phase, spending about $3,100 dollars out of pocket on average. A substantial percentage of people similarly situated this year will save significant money by avoiding further costs after hitting the cap. According to the HHS brief, 636,000 Part D enrollees will save more than $1,000 this year, and 1.9 million will reach that threshold when the cap drops to $2,000 next year, with an average savings of $2,500 each. (These totals include a small total of enrollees who will be newly eligible for full instead of partial LIS. The IRA raised the income eligibility threshold for full LIS benefits from 135% FPL to 150% FPL.) The brief also tracks savings from the insulin price cap and free vaccines. Taking all these provisions into account, HHS projects that 1.1 million Part D enrollees will save more than $500 this year and 3.3 million in 2025 as a result of the IRA.

Antitrust scrutiny. Aggressive action to reduce healthcare market concentration on multiple fronts — in hospital systems, between hospital systems and physician practices, in vertical integration by insurers and national pharmacies (buying physicians practices, pharmacy benefit managers, technology vendors), and in private equity rollups (of physician practices in targeted specialties and regions, nursing homes, hospice, and various other types of specialty care) — could ultimately prove the most consequential action taken by the Biden administration to control costs, albeit the slowest to take effect. The Biden FTC and DOJ are the most active in merger challenges and aggressive in regulation in generations. The FTC has issued significantly tightened merger guidelines for all industries. New standards with particular relevance to healthcare include a lower threshold for considering a given market highly concentrated, and increased scrutiny of multiple acquisitions that may individually fall beneath the threshold that acquirers must report.

In March, the FTC, DOJ and HHS launched a public inquiry “into private-equity and other corporations’ increasing control over health care,” issuing a request for information on consolidation in healthcare markets, with particular focus on

transactions in the health care market conducted by private equity funds or other alternative asset managers, health systems, and private payers, especially those transactions that would not be noticed to the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, 15 USC 18(a). These transactions could involve dialysis clinics, nursing homes, hospice providers, primary care providers, hospitals, home health agencies, home- and community-based services providers, behavioral health providers, billing and collections services, revenue cycle management services, support for value-based care, data/analytics services, and other types of health care payers, providers, facilities, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs), or ancillary products or services.

To facilitate this effort the agencies have created a portal for “public reporting of anticompetitive practices in the healthcare sector.” The FTC has also filed suit against private equity firm Welsh Carson and its portfolio company U.S. Anesthesia Partners, a behemoth which executed, in FTC chair Lina Khan’s description, “a multi-year roll-up strategy to buy nearly every large anesthesiology practice in Texas and stomp out independent providers.”

The FTC and DOJ have also boosted cooperation with each other and with state attorneys general to increase antitrust enforcement in healthcare. States in turn are ramping their requirements for state AGs to conduct pre-merger antitrust reviews of healthcare transactions, at dollar value thresholds lower than the federal standard. A number of states have passed new laws ramping up reporting requirements for transactions in the healthcare industry and in some cases increasing state government authority to block transactions.

None of these initiatives refute Axios’s contention that steadily rising healthcare costs may dampen voters’ enthusiasm for the Biden administration’s touted accomplishments in healthcare. Healthcare costs do rise relentlessly; consolidation gallops on; creative new forms of rapine arise all the time. It’s also true that the Medicaid unwinding is “unwinding” some of the coverage gains of recent years and causing considerable pain and harm to millions. Short of a structural overhaul of the behemoth healthcare industry, however — which would require currently unimaginable Democratic majorities and probably, an equally fundamental overhaul of campaign financing — it’s hard to imagine an administration under current political conditions acting more vigorously or effectively to control costs on various fronts. Voters do give Democrats considerable credit for their healthcare stewardship — though admittedly, as Axios emphasizes, the most recent KFF poll indicates that their political advantage in healthcare matters does not extend to the question of cost control (per the bottom question below).

No comments:

Post a Comment