Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up!

If you’ll excuse an off-topic post, a graduate school friend of mine (circa 1990…), Wendy Bashant, has published a truly memorable account of her year teaching at a “Chinese MIT” - interrupted but not derailed by the pandemic. The book opens a real window into the minds of Chinese students — elite but not necessarily privileged. Their writings, liberally excerpted, reflect a huge variety of childhood experiences in a country that contains multitudes. The book is The Same Bright Moon: Teaching China’s New Generation During Covid. My Amazon review is below.

* * *

After decades serving as a dean at various U.S. colleges and universities, Wendy Bashant was burned out and ready to return to her teaching roots and meet the minds of students in a distant land. With her equally willing physician husband, she landed in mid-2019 at Jiaotong University in Xi'an, a megacity in central China, tasked with teaching American literature and writing at a school she describes as MIT-equivalent. In the course of a teaching year, she also experienced a pandemic, Chinese-style: emergency travel through a ghosted airport; swift, strict lockdown; partially successful experiments with remote teaching; and gradual return to something like normalcy under a regime of strict, unquestioned rules.

A passionate and empathic teacher, Bashant managed to form deep connections and spur original thought from a significant number of her students. She shares their reflections on their childhoods, their aspirations, and how they think the world works through conversation (in-class and one-on-one) and through the students' essays and poems. The writings and conversations offer a series of truly illuminating windows into young Chinese adults' varied experiences and mindsets. One reality that comes through very clearly is that China contains multitudes: the students' home environments range from rural villages to megacities (and often to both, as one recurring pattern is parents working in the city while their children live with grandparents in the home village), their parents from professionals or government officials to laborers with minimal education. The students have lived through decades of rapid change; often their parents' experience is radically different from their that of their grandparents, and the students’ essays describe these discrepancies.

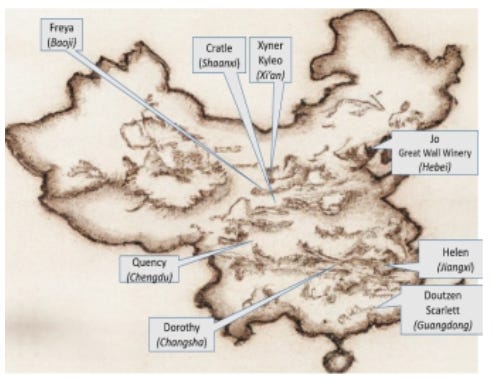

Bashant develops a rather lovely framework to encompass this diversity, adapting the (fading) Chinese tradition of the "hundred family jacket," in which local families donate embroidered cloth patches to a newborn's family, to be sewn onto a jacket that's worn at festivals. Bashant's "jacket" is a map of China in which she places various students, chapter by chapter (initially, as a device to remember their names), as their narratives reflect the diverse regions and cultures in which they grew up, from open plains near Mongolia to small dark grandparents' apartments in megacities. This works, because the students' essays do take us to these places.

While these students have been studying English since they were 5 (Bashant tells us), English is a second and very foreign language. The essays reflect this -- along with, to my ear, a sometimes reflexive reliance on authority -- governmental, parental, commercial -- to frame the writer's thoughts. The book's drama comes in large part from students' efforts -- sometimes stunningly successful -- to break out of conventional wisdom and think for themselves.

Bashant gives a vivid account of the physical privations and social pleasures of living in a 60s-era Chinese apartment block that houses the university community, ranging from professors to custodians. The Bashants are showered with food, invited to residents' family homes outside of town, helped through logistical difficulties. You have to credit their resilience and willingness to embrace new experience. I would have liked to hear a bit more about the experience and perspective of husband David, who worked as a tutor and translator of scientific texts at the university.

While antagonism between China and the U.S. was not as intense in 2019 as now, it was rising quickly, and turbo-charged during the pandemic as Trump unleashed his incontinent verbal fury at China. The Bashants are asked constantly about Trump and about American attitudes toward China. Bashant's students voice some negative perceptions about Americans and America, but these do not seem to impede their relationship with her -- at least not for the students whose experience she chronicles and records. Bashant does not really engage politically (there would be severe constraints on doing so in China, I imagine). There are no discussions of Trump either as appalling anomaly or true expression of the worst American traditions. Nor does Bashant engage with escalating authoritarianism in China. Indeed, she seems receptive to positive aspects of Chinese governance -- that is, the tight restrictions and preventive procedures (many of which proved to be mistaken epidemiologically) in the first months of the pandemic.

That said, The Same Bright Moon fulfills the premise of its title: that minds can meet across cultures, that we can process the common elements of human experience very differently, while communicating and gaining some understanding of these differences; that on an individual level at least, empathy can bridge continents.

No comments:

Post a Comment