Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up.

|

| CMS to Texas: Who told you to put the balm on? |

As expiration of the enhanced ACA premium subsidies created by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) at the start of Plan Year 2026 looms, it’s worth considering the extent to which strict silver loading may mitigate the sharp premium increases resulting from reversion to the ACA’s original subsidy schedule. Here we’ll take a look at how a market in which gold plans are priced way below silver in 2025 is likely to play out in 2026.

If you’re reading this blog, you probably know what “silver loading” refers to. In brief: it’s the practice of pricing the value of Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR), which attaches to silver plans for enrollees with income up to 250% FPL, directly into premiums for silver plans. Doing this was rendered possible/necessary when Trump cut off direct reimbursement to insurers for the value of CSR in October 2017. Since CSR raises the actuarial value of a silver plan to a roughly platinum level at incomes up to 200% FPL, and most silver plan enrollees are below that income threshold, silver plans’ average actuarial value exceeds that of gold plans — so gold plans should be cheaper than silver. Since marketplace subsidies are structured so that enrollees pay a fixed percentage of income for a benchmark silver plan, pricing CSR into silver raises subsidies along with silver premiums, making plans that are cheaper than the benchmark more affordable.

In practice, silver loading is usually only partial, as insurers have several incentives to underprice silver plans. Several states, however, have mandated “strict” silver loading, directing insurers to price plans at each metal level in strict proportion to their average actuarial value (which for silver plans is higher than gold’s 80% AV in most states). A handful of states have gone further, directing insurers to assume that all silver plan enrollees have income below 200% FPL, i.e., that silver plans have an AV of about 90%. That’s meant to be a self-fulfilling prophecy: if gold plans are cheaper than silver plans, no one with an income over 200% FPL has any reason to select silver.

In 2025, the average lowest-cost gold plan is priced below the average benchmark silver plan in fourteen states.* The most notorious “strict silver loader” is Texas, which passed a law mandating premium alignment in 2022 and fleshed it out with regulation pegging silver plan premiums at a platinum level in 2023 and years following. (That’s fully justified, because the average AV obtained by Texas silver plan enrollees exceeds 90%. More than three quarters of the state’s enrollees have income below 200% FPL, as do 96% of silver plan enrollees.) At incomes over 200% FPL, gold plans have a higher AV than silver plans, and since they also have far lower premiums than silver plans in Texas, gold dominates silver at incomes above 200% FPL.

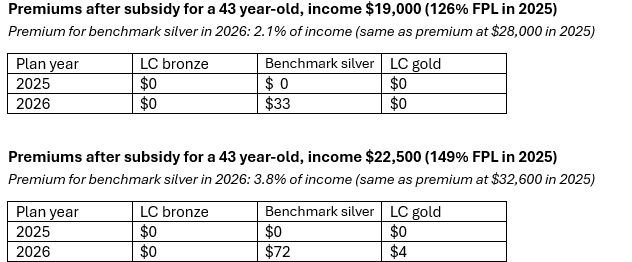

To get a sense of the (limited) extent to which strict silver loading may mitigate the loss of the ARPA-enhanced subsidies, let’s zoom in on Houston, the largest market in Texas. For a 43 year-old in Houston, the lowest-cost gold plan is priced at $68 per month lower than the benchmark silver plan. That will matter a lot for enrollees with low incomes when silver once again carries a premium. For many enrollees, the zero premium attached to one or more gold plans will likely outweigh the large difference in OOP max that is high-CSR silver’s most important advantage.

Below is the marketplace’s subsidy schedule** for 2026, compared to the ARPA-enhanced schedule in effect now, in 2025.

Percentage of income required to purchase a benchmark silver plan at different income levels, under ARPA and post-ARPA

To estimate what options may look like in 2026 in Houston, I calculated how much a single adult (43 years old) will pay for benchmark silver at various incomes in 2026.** Using HealthSherpa’s plan preview tool, I then found the income level*** at which a person would pay the same premium in 2025 (approximately $10,000/year higher than in 2026) and identified lowest-cost bronze and gold plans at that income. The value of this hypothetical depends on price spreads between metal levels staying more or less the same in 2026 as in 2025 in this market.

Here, first, is an overview of out-of-pocket cost exposure for the benchmark silver and lowest-cost bronze and gold plans in Houston in 2025. The four levels of silver reflect the three levels of CSR (AV 94%, 87% and 73%), along with silver with no CSR (AV 70%). Bronze AV is 60%, and gold is 80%.

At incomes up to 200% FPL (scenarios 1-3 below), silver plans have a higher actuarial value than gold plans (94% or 87% vs. 80%). The difference is reflected most dramatically in the out-of-pocket maximum, which is capped at $3,000 for silver plans up to that income threshold, compared to $8,000 for lowest-cost gold.

Let’s look first at the choices at the income brackets where silver plans carry the highest CSR-enhanced actuarial value, 94%: up to 138% FPL and up to 150% FPL.

The most important tradeoff here is premium vs. annual out-of-pocket maximum: $2,000 for silver vs. $8,500 for gold. For those who don’t anticipate needing a lot of medical care, though, $0 premium or $4/month gold is likely to outweigh the increased out-of-pocket risk. For some enrollees in the 138-150% FPL bracket, free bronze may trump even the relatively minimal gold premium (particularly if enrolled by the kind of unscrupulous broker that has plagued the market in recent years, as any premium at all increases the odds of disenrollment).

I should add, too, that the cheapest silver plan, also from Ambetter, is a not-insignificant $11/month cheaper than the benchmark. Its deductible is much higher ($800 at this income level), but its out-of-pocket max is lower (also $800). It thus might attract both those for whom $22/month sounds a lot better than $33/month and those who know they’ll need to spend more than $1,000 on medical care in the year.

Of course, premium and out-of-pocket cost structure are not the only important variables. In Texas, where provider networks tend to be extremely narrow, significant numbers of enrollees pay more for plans with more robust networks.

A bottom line at these income levels (up to 150% FPL) is that $0 premium coverage is likely to remain available — nationally as well as in Houston, albeit usually bronze. That may limit exodus from the market to some extent among the 11 million current enrollees in the 100-150% FPL bracket nationally — though new enrollment barriers will cut the other way, and hundreds of thousands of lawfully present noncitizens lacking green cards will be cut out entirely.

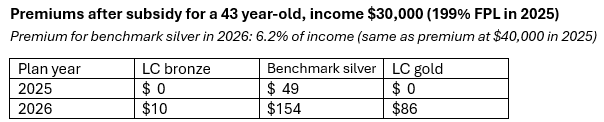

Next up is an income level, 150-200% FPL, where choices will degrade more sharply in Texas in 2026 — and where the substantial out-of-pocket cost protection provided by CSR is likely to feel out of reach for many enrollees.

Staring down that benchmark silver premium, it’s hard for me to fathom that in 2017, 83% of enrollees in the 150-200% FPL bracket chose silver plans. That was before an enormous influx of low-income enrollees into the marketplace, driven by the ARPA-enhanced subsidies and a near-doubling of brokers participating in the market. Enrollment in the 150-200% FPL bracket has more than doubled since 2017, from 2.0 million to 4.3 million in 2025. Meanwhile, provider networks on average have narrowed and both net-of-subsidy premiums and out-of-pocket costs have risen. In 2017, the Benchmark silver premium for enrollees with income just below 200% FPL was I believe in the $120/month range. The out-of-pocket max at this income level averaged $1,875 in 2017, vs. $2,859 in 2025, per KFF. There was as yet no silver loading, and spreads between bronze and silver premiums were smaller.

All of which is a long windup to suggest that it’s hard for me to imagine many enrollees in this income bracket choosing silver from the menu above— unless they know that their out-of-pocket costs are likely to exceed silver’s much lower OOP max. Gold may be the choice for some who anticipate significant but more moderate medical expense.

The availability of zero-premium coverage has been shown to have a significant impact on enrollment, as any administrative friction at all (e.g., making a first payment to an insurance company, which the carriers don’t always make easy) tends to drive people out of the market. Before the ARPA subsidy enhancements, the advent of silver loading in 2018 made zero-premium bronze newly available to millions. At the income producing the choice menu above ($40,500 this year, $30,000 in 2026), the lowest-cost bronze premium zeroes out at age 46, since spreads increase along with premiums as age rises. ARPA expiration is likely to increase the average enrollee age, as net-of-subsidy premiums for plans cheaper than the benchmark shrink as age increases.

Moving on now to upper the income brackets that will remain subsidy-eligible in 2026:

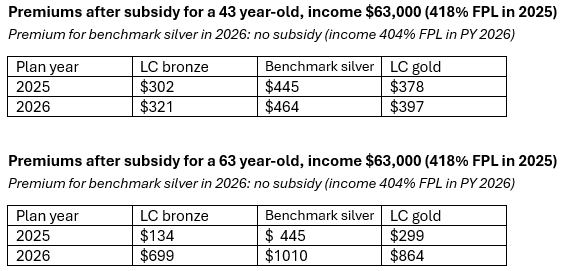

First to note is that a lot of people in upper income brackets are losing free coverage. The leap in the lowest-cost bronze premium at the fairly modest income of $37,600 is striking (though again, it shrinks as age rises).

If you rub the ARPA-enhanced subsidies out of your vision, the gold premium discount in this market looks pretty attractive at these incomes. At the $45,200 income level, 289% FPL in 2026, while benchmark silver will cost 9.8% of income, lowest-cost gold will cost just 8.0% of income if this year’s silver-gold premium spread holds. That “discount” is not nothing. The lowest-cost gold premium remains below the ARPA-enhanced maximum for benchmark premiums, 8.5% of income.

Note too that silver plans are completely dominated by gold in Texas at incomes over 200% FPL. At incomes over 200% FPL, silver’s actuarial value is substantially lower than gold’s, and its premium is higher. End of story.

Finally, let’s look at what happens when income crosses the newly re-established cap on subsidy eligibility, 400% FPL.

In 2025, the 43 year-old with income slightly over the once and future subsidy cap benefits only modestly from the absence of a cap, as premiums in Texas are among the lowest in the country. (In Anchorage, Alaska, the same 43 year-old’s monthly subsidy would be $716 instead of $19, as benchmark silver with no subsidy would be $1087/month.) At age 63, however, the loss of this year’s subsidy limiting the benchmark premium to 8.5% of income regardless of income is pretty catastrophic — especially for a near-elderly couple.

This year, Illinois enacted a law mandating strict silver loading in Plan Year 2026. New Jersey also has a bill pending, S1971, that would mandate pricing silver plans at their average actuarial value in year 1 and mandate pricing them at 90% AV in year 2. (Gold plans are uniquely unaffordable in New Jersey, and have been since the ACA marketplace’s launch in 2014.) That bill is unlikely to advance, though. States considering strict silver loading mandates need to reckon with a Trump-era CMS that may ban the practice, requiring that the CSR load be evenly distributed across all metal levels. Under Trump’s CMS administrator Peter Nelson, CMS’s primary concern, as evidenced in the so-called “Marketplace Integrity and Affordability Rule” finalized in June, seems to be minimizing the marketplace’s cost to taxpayers. As silver loading increases premium subsidies, it’s reasonable to suspect that its future is doubt.

- - -

Notes

* In 2025, the average lowest-cost gold plan is priced below the average benchmark plan in Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Iowa, Maryland, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming. In some of these states, cheap gold plans are available because a dominant insurer chooses to make it so; others mandate “premium alignment” with metal level AV by regulation or legislation. A new law mandating strict silver loading goes into effect in Illinois for 2026.

** KFF estimated last July that average ACA enrollee premium payments will increase by more than 75% (with wide variation, as the scenarios below illustrate). But that year-old estimate is low, as the “applicable percentages” of income required to buy benchmark silver in 2026, published by the IRS this month, are well above the percentages KFF estimated a year ago — almost a full percentage point higher in some brackets. KFF’s calculator, estimating how much more any given enrollee will pay for the benchmark (second-cheapest) silver or cheapest bronze plan if the enhanced subsidies expire, uses last year’s estimated subsidy schedule, and therefore lowballs how much enrollees will pay in 2026.

*** At the selected income levels, FPL in 2026 will be 5-11 percentage points lower than in 2025. To find the applicable percentage for the lower 2026 FPLs, I used the method laid out by the indispensable Louise Norris here. Louise pulled the information from the formula laid out in CFR 1.36B-3. Of course she did.

No comments:

Post a Comment