Note: All xpostfactoid subscriptions are now through Substack alone (still free), though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up!

In October, CMS reported that of the roughly 5.5 million people disenrolled from Medicaid from the start of the “unwinding” (the end of the pandemic-induced 3-year moratorium on Medicaid disenrollments) through July 31, about 600,000 (592,291) had enrolled in ACA marketplace coverage. Another 95,000 enrolled in the Basic Health Programs that in New York and Minnesota serve lower income enrollees who would otherwise be eligible for subsidized marketplace coverage.

As Charles Gaba notes, these tallies suggest that about 12% of those disenrolled from Medicaid from April to July have enrolled in marketplace or BHP coverage. If that ratio held into November, about 1.1 million of the 10.1 million disenrolled from Medicaid according to KFF’s estimate may have ended up in the ACA marketplace. According to tracking by Georgetown’s Center for Children and Families, as of October, based on the most recent state reports ranging from July to September, net Medicaid enrollment was down by 5.8 million. Assuming that net disenrollment might top 7 million by now, the marketplace may have insured about 15% of the net coverage loss, perhaps a bit higher for adults (as most children who are not insured through employment-sponsored plans end up in Medicaid or CHIP). Here’s hoping a larger percentage of the newly disenrolled find coverage from employers — or already have done so, and have been double-insured since some point after Medicaid redeterminations were paused in March 2020.

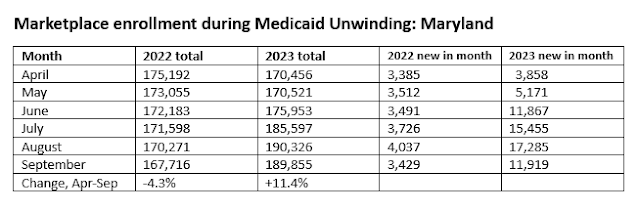

While the marketplace is taking up only a modest sliver of those disenrolled from Medicaid, the influx represents a substantial boost to marketplace enrollment. David Stewart, Health Insurance Program Director at the Maryland Area Health Education Center West, which serves primarily rural counties, tells me that since May, appointment traffic for enrollment assistance in his program was more than double normal volume prior to the Open Enrollment Period that began on November 1. To get a sense of how that increase in interest might translate in enrollment I went to the Maryland Health Connection in search of data, and to my surprise, found detailed monthly reports. And indeed, new enrollments from May through September in Maryland in 2023 were more than triple the 2022 total. While enrollment in Maryland as of April 2023 was down 2.7% from April 2022, enrollment as of September 2023 was 13.2% higher than in September 2022.

According to the Georgetown disenrollment tracker, net Medicaid enrollment in Maryland dropped by 60,529 from May through September 2023. The state marketplace tallies above show that marketplace enrollment increased by a net 19,334 from May through September. The ratio of net marketplace increase to net Medicaid decrease in Maryland appears to be considerably higher than in the country as a whole. That’s not surprising: Maryland state agencies, according to Stewart, are oriented toward maximizing coverage.

In a conversation last week, Stewart told me that his organization works closely with local officials in the Maryland Department of Health; enrollment officials can contact Medicaid supervisors and caseworkers directly and troubleshoot problems in real time. Unlike in most states, Maryland Health Connection, the state ACA exchange, not only processes Medicaid enrollments directly — it is also the primary vehicle for Medicaid applications. An integrated platform for enrollment in a wide array of government benefits, MDThink, is scheduled for full implementation in early 2025.

The fact that marketplace and Medicaid enrollment are in the same system, Stewart said via email,

helps us with things like procedural drops (when the system incorrectly takes someone out of MA [Medical Assistance, the Maryland term for Medicaid]. Health Department, Social Services case workers and my navigators all have access to the same information. It helps tremendously when resolving problems for a particular person. Case workers can take an application all the way to plan selection and hand off to us. We do the same for MA cases and hand off to them when it is a more complicated case…

Because Medicaid and QHPs are in the same system, collaboration between navigators and case workers is easy. We can read each other’s case notes for example. We can see who last worked with a consumer. And while case workers do not assist with QHP plan selection, it is incredibly helpful for my navigators to receive an application which is ready for plan selection. We know we can trust the work of the HD. This year with the “unwinding” everybody in the system is experiencing much higher appointment volumes. It saves us precious time. The advantages of being in the same system are born out every day.

That Medicaid case workers will “take an application all the way to plan selection” indicates a level of administrative support and system integration that I believe is quite rare in this country. According to the CMS’s State-based Marketplace Unwinding Report, Maryland is one of four states (with CA, MA and RI) enabling “automatic QHP selection” in the unwinding — though according to Stewart, the state Health Department completes the application but does not select/enroll the applicant in a particular plan. Through July, according to CMS data, more than 8,000 enrollments in Maryland were automatic.

This is not to imply that the unwinding in Maryland is smooth sailing, or that state systems are glitch free. The state has had its share of “procedural drops” — for example, dropping a whole family when one member is found ineligible. But at least in the rural counties Stewart works in, the Health Department will respond promptly when such a drop is brought to their attention and swiftly restore coverage, which in such cases is retroactive. “The environment is pretty pro health insurance,” Stewart says.

One mystery in CMS’s tracking of Medicaid-to-marketplace conversions is the extremely low percentage of subsidy eligibility in some state-based marketplaces among those who are disenrolled from Medicaid and seek marketplace coverage. Maryland is among them: only 41% of Medicaid “unwinding” disenrollees determined eligible for marketplace coverage are eligible for subsidies (see Gaba’s chart here). Other states with a low subsidy-eligible ration are Kentucky (25%), Vermont (43%), California (45%) and Minnesota (47%). Nationally, the percentage of “unwinding” applicants deemed marketplace eligible who are also subsidy eligible is 74%. During the Open Enrollment Period (OEP) for 2024 coverage, the percentage was 86% for all states, and 73% in SBM states. As Gaba points out, the subsidy-eligible percentage is much higher in the states that have refused to enact the ACA Medicaid expansion, all of which use the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov. In Florida, 91% of Medicaid disenrollees deemed eligible for marketplace coverage are subsidy-eligible, as are 86% in Texas. Those two states together account for 32% of “unwinding” enrollees.

Marketplace applicants can be ineligible for subsidies mainly for two reasons: unsubsidized benchmark coverage (the second-cheapest silver plan) costs less than 8.5% of their household income, or they have access to other coverage deemed affordable, usually employer-sponsored coverage. In the unwinding, a higher percentage of enrollees are subsidy-ineligible than in OEP for 2023; ; in Maryland, the gap is particularly wide — 59% ineligible for subsidies in the unwinding vs. 39% in OEP. It may be that a substantial number of people with considerable earning power who lost jobs early in the pandemic were “frozen” in Medicaid and now earn too much to qualify for marketplace subsidies. Maryland does have the third-lowest average benchmark premiums in the nation ($346/month for a 40 year-old, vs. $477/month nationally). In Baltimore, a 26 year-old earning $40,000, or a 30 year-old earning $44,000 annually, would be ineligible for subsidies. Many may also report that they are eligible for employer-sponsored coverage, though it’s unclear why that percentage would be higher than in OEP.

If anyone has other ideas as to why so many Medicaid disenrollees who apply for marketplace coverage are not subsidy eligible, please let me know.

Photo by Ketut Subiyanto

No comments:

Post a Comment