|

| Meaningful difference? |

In its proposed annual set of rule adjustments* for the ACA marketplace for 2024 released yesterday, CMS proposes strong action against one of the marketplace’s most counterproductive current features — the proliferation of plan offerings insurer with all-but-invisible differences between plans.

In many ACA markets, several insurers “spam” the marketplace, as Duke health insurance scholar David Anderson puts it, in this way. In such markets, picking a plan that will minimize your medical expenditures is like trying to pick the most cost-effective choice in your supermarket’s toilet paper aisle.

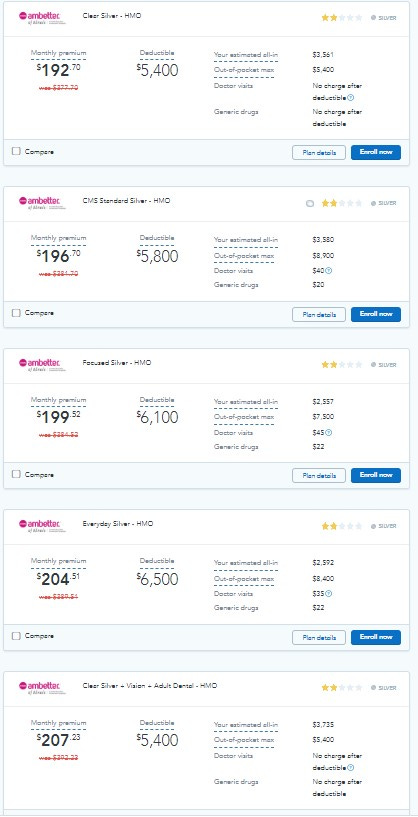

Here, for example, are the five cheapest Ambetter silver plans available in Chicago. (Quoted premiums** are for a single 40 year-old with an annual income of $40,000.)

Here are the next five.

I will spare you the next five. That’s right — Ambetter has put up 15 silver plans in the Chicago marketplace.

As a rule, the cheapest insurers offering the narrowest networks are major offenders on this front. (Almost no major hospitals are in-network in Ambetter’s Chicago plans.) In many markets, their near-clone offerings render competitors’ products nearly invisible at the lowest price points. (That’s not quite the case here, as Oscar’s 12 silver plans and BCBS’s seven are interspersed with Ambetter’s at low price points.)

In the 33 states that use the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov, as well as in eleven of the 18 state-based marketplaces, plans with a standardized benefit structure — the same deductibles, copays, annual maximum out-of-pocket limits (MOOP) and services not subject to the deductible — are available at each metal level. Squint at the offerings displayed above and you’ll see that the second one is marked “standard.” But standard plans swim in a sea of non-standard competitors. While their benefit design may be optimal for average (not all!) applicants, they have nothing obvious to recommend them — not the lowest premiums, nor deductibles, nor MOOPs, nor standard copays.

With 137 plans on offer, Chicago is not the most chaotic marketplace in the country. In fact, it’s not too far off average. The average number of plans available to marketplace applicants in 2023 is 114, up from 26 in 2019, as CMS notes in its proposal to reduce this riot of unmeaningful choice. In Miami, the nation’s largest ACA marketplace, 224 plans are on offer.

How was this mass spamming of the marketplace allowed to metastasize? In 2015, CMS established a standard to ensure that that plans offered by the same insurer be “meaningfully” different. But the standard was toothless, as Anderson points out, and in advance of the plan year for 2019 the Trump administration’s CMS administrator, Seema Verma, did away with it entirely. The primary rationale, according to CMS’s account in this year’s proposed rule (pg. 230 here), was that the number of insurers participating in the exchange had shrunk in the Trump years (there was real anxiety about the possibility of “bare” rating areas where no insurers would participate). But it also reflected Verma’s was ideological commitment to proliferating choice in every health insurance market (including the choice of medically underwritten, lightly regulated, ACA-noncompliant plans).

While markets had indeed contracted after major premium spikes in 2017 and 2018 (the latter triggered by Republicans’ threatened repeal and the Trump administrtion’s regulatory assault on the marketplace), from 2019 forward ACA markets first stabilized and then expanded, with insurers returning to the marketplace and entering new states. The Biden administration has not reinstated (let alone strengthened) meaningful difference regulations — until now.

For 2024, CMS proposes to take a path forged by some state marketplaces and limit the number of nonstandard plans an insurer can offer in a given market. Specifically, the proposal (as summarized on this fact sheet) is

to limit the number of non-standardized plan options that issuers of QHPs can offer through Marketplaces on the Federal platform (including SBM-FPs) to two non-standardized plan options per product network type and metal level (excluding catastrophic plans), in any service area, for PY2024 and beyond, as a condition of QHP certification.

Theoretically, if an insurer offered three network types (HMO, EPO, PPO) at four metal levels, it could still offer 36 plans in one market. But that will not happen. PPO plans are rare in the marketplace, as are platinum plans. Note in the display above that Ambetter (a Centene brand), probably the most prolific spammer in the country, offers only HMO plans. In fact this regulation, if implemented as proposed, may increase meaningful difference among plans, as insurers seeking to differentiate themselves may be moved to vary their network types.

At present this rule is only “proposed.,” and so subject to a comment period, response, and possible revision or withdrawal. As an alternative, CMS floats a “meaningful difference” standard stronger than the previous one but less restrictive than the main proposal: Requiring that the deductibles offered by one insurer in a given metal level and network type vary by at least $1,000. That’s presumably harder to do than, say, offer a $20 copay for a primary care visit and $10 charge for generic drugs in one plan versus a $25 PCP visit and $5 generic drug charge in an alternative.

The primary proposal would require a major change in business model for some of the largest marketplace insurers — and, I think, a much improved choice architecture for prospective applicants. Here’s hoping that CMS follows through.

Update, 12/14/22: Over on Mastodon, David Anderson warns that considerably more than three network variations per insurer per metal level are conceivably allowable (and in the same exchange, Louise Norris points out that POS (Point of Service) networks are another network type). Putting up multiple networks, however, is much harder (and more substantive) than fine-slicing the odd co-pay to field a new plan. I would speculate, too, that incentivizing insurers to offer more PPOs might in fact be beneficial. Meanwhile, Charles Gaba, also surveying this proposed rule change, deploys the cultural reference that inevitably comes to mind when surveying the proliferation of plans: Robin Williams freaking out in the coffee aisle in Moscow on the Hudson. That’s more fun than my Honey Crisp-to-Mackintosh contrast. Charles also provides useful backstory on meaningful difference regulation, or the lack thereof.

- - -

* The annual rule updates are known as the Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters. The full proposed rule for 2024 is available here.

** The display is from HealthSherpa, a commercial Direct Enrollment broker that displays all plans in all markets that use HealthCare.gov.

No comments:

Post a Comment