Note: Free xpostfactoid subscription is available on Substack alone, though I will continue to cross-post on this site. If you're not subscribed, please visit xpostfactoid on Substack and sign up

|

| Heavy OOP burden |

You may have read KFF’s estimate that the average subsidized 2025 enrollee in the ACA marketplace will pay 114% more* for a benchmark silver plan in 2026, if the enhanced subsidies funded only through 2025 are allowed to expire. True!

You may also have read estimates that base (unsubsidized) premiums will rise 25% (from Charles Gaba) or 26% (from KFF). Also true!

Now, as of today, you may read CMS’s proud assurance (via https://www.axios.com/2025/10/28/trump-open-enrollment-premium-prices-health-care-government-shutdownAxios) that things are not so bad:

These claims are doubtless also true! How can that be? Are premiums for subsidized enrollees going up 114% — or 35%? (i.e. from $37 to $50/month, per CMS**).

It depends, of course, on the plan you’re buying and what percentage of your actual medical claims it will cover. The KFF estimate is for the benchmark (second cheapest) plan — the one for which all subsidy-eligible enrollees pay a fixed percentage of income, which is being sharply reduced. The actuarial value of a silver plan varies with income, but for most enrollees it’s 94% or 87% (ratcheting down to 73% or 70% at income above 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

The CMS estimate is for the cheapest plan in a given rating area — that is, a bronze plan, with an actuarial value around 60% and a deductible likely north of $7,000 (though not always — there are zero-deductible bronze plans as well). (Update: As Charles Gaba points out, The Onion has showcased pitches like this one.)

Many enrollees with income below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) — that is, a majority of enrollees — may be tempted or forced to trade a silver plan enhanced with Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR), with a single-person out-of-pocket maximum that can’t exceed $3,500 (and is usually lower, averaging $1595 for those with income up to 150% FPL in 2025) for a plan with an OOP max at or exceeding $8,500 and often carrying the maximum allowable $10,600.

Why is the lowest-cost bronze plan’s premium lower on average in 2025 than in 2020? Well, benchmark premiums are up 30% this year (also according to CMS) on top of a modest 7.6% rise from 2020-2025. When benchmark premiums rise, so do premium subsidies — and so, on average, does the “spread” between the benchmark premium and premiums for cheaper plans (e.g., the cheapest silver plan, most bronze plans, and, in fifteen or more states, some gold plans).

CMS is also touting the OBBBA provision that made all bronze plans so-called High Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs) that can be paired with a tax-favored Health Savings Account (HSA). HSA contributions reduce an enrollee’s Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) and so increase the premium subsidies by whatever amount is contributed. Call it a MAGA MAGI. Of course, low-income people (e.g., most marketplace enrollees) rarely have excess income to stuff into a dedicated account.

Further relief for the subsidy-eligible, as I’ve pointed out before, comes from strict silver loading in fifteen or more states that renders gold plan premiums cheaper than (or in a few cases, roughly on par with) benchmark silver plans. Very briefly: thanks to CSR, which attaches only to silver plans, the average silver plan enrollee (i.e. an enrollee with an income below 200% FPL) has a plan with a roughly platinum value (actuarial value 94% or 87%) — higher than gold’s 80%. CSR has been priced directly into premiums ever since Trump cut off direct payments to insurers for it in October 2017. Some states have mandated that plans at each metal level be priced in strict proportion to their average actuarial value, or even that silver plans be priced as if they always carry an AV of 94% or 87% (as, in states like Texas that haven’t expanded Medicaid, they almost always do). In advance of Plan Year 2026, Arkansas, Washington, and Illinois have newly required “strict” silver loading, bringing the likely number of states in which gold plans are cheaper than silver to about 18 (we won’t know until all 2026 premium data is in).

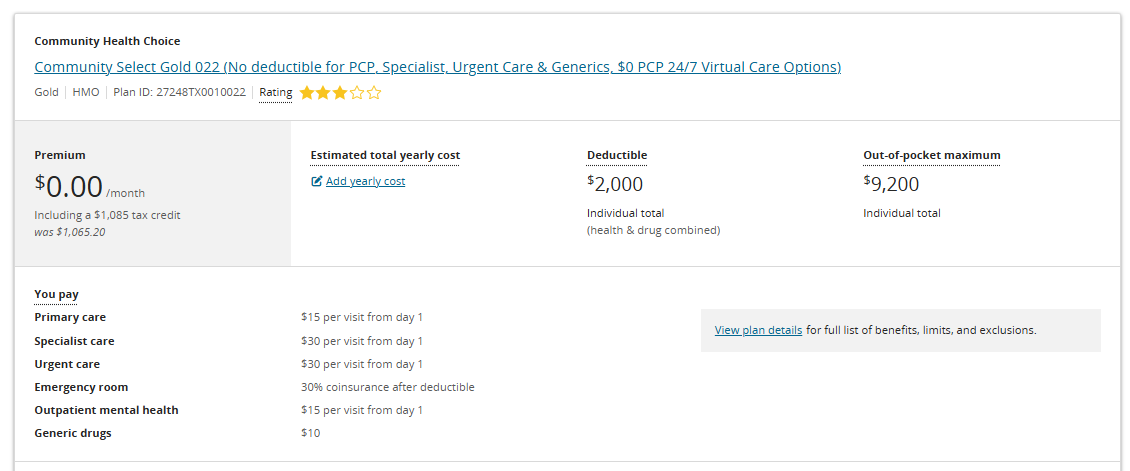

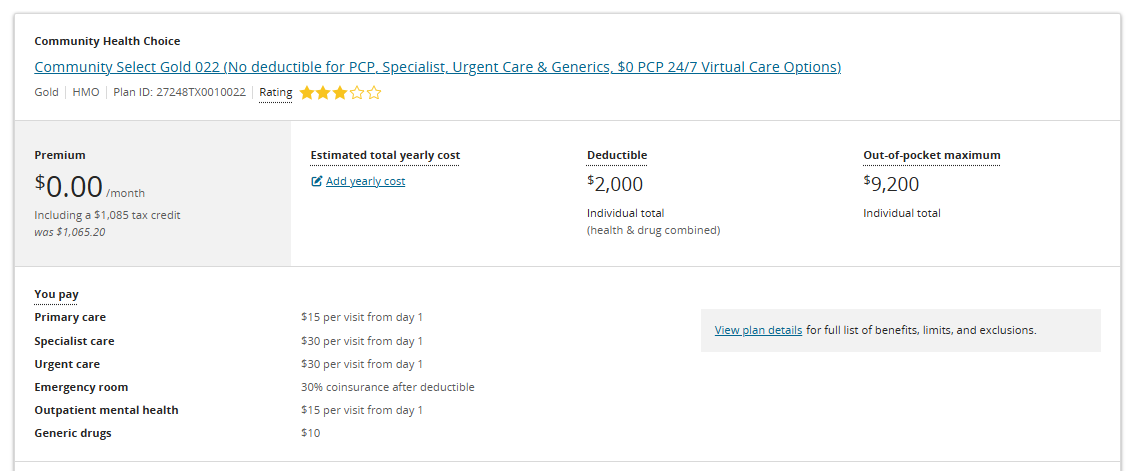

In Texas, which has almost 4 million marketplace enrollees, gold plans have been priced far below benchmark since 2023. This year, zero-premium gold plans will be available pretty far up the income chain. HealthCare.gov has just today loaded 2026 plans into its plan shopper, so let’s take a look:

Houston, zip code 77011, single 60 year-old, income $31,300 (200% FPL) (cheapest silver $160/month)

The same plan is available at zero premium to two 43 year-olds earning $30,012 annually (175% FPL).

I cheated a bit by showcasing a 60 year-old. As premiums rise with age, so do subsidies, and so do premium spreads. A single 43 year-old at 200% FPL in Houston would pay a bit more than $70/month for the cheapest gold plan.

These mitigations are very partial. For subsidized enrollees, marketplace choices are in some ways better than in 2020, and in some ways worse (e.g., with higher out-of-pocket maximums). In that year, 11 million people enrolled — compared to 24 million 2025. Marketplace takeup among subsidy-eligible people who lacked other insurance was well below 50% before the American Rescue Plan Act enhanced subsidies in March 2021.

The expansion of HSA availability, coupled with increased spreads between benchmark and bronze premiums, in some ways create a Republican dream market, where the default option for many of those who need coverage is essentially catastrophic coverage (deductibles north of $7,000, OOP maxes north of $10,000). A rational Republican party seeking to reshape the ACA in 2017 might have come with a market that looks something like OEP 2026 if the subsidies are not extended. For Republicans, increasing the uninsured population by perhaps 50% — as their Medicaid cuts coupled with the pending marketplace subsidy cuts will likely do if not amended — is just the cost of “free” markets.

—

*The KFF estimate of increased net-of-subsidy premium costs includes about 20 million enrollees who will see their subsidies reduced (as a percentage of income they have to pay for the benchmark) and about 1-2 million who will be rendered ineligible for subsidies as the income cap on subsidies (400% FPL) snaps back into place.

** The 35% increase is a correction; originally I pegged the increase reported by CMS at 26%.

No comments:

Post a Comment